Building Family-Professional Partnership Infrastructure from the Start

Partnership infrastructure matters in a moment when families need to trust programs with their children's safety. Partnership infrastructure is not a nice-to-have. It is what makes trust possible.

This piece builds on my prior work examining practice architectures for NYC's early childhood expansion and building educator capacity for responsive care.

——

New York City is investing approximately one billion dollars per year in 2-Care (Kramer, 2026). Governor Hochul and Mayor Mamdani announced in January 2026 that New York State will fund the first two years of this free child care program for two-year-olds, launching fall 2026. Combined with existing 3-K and Pre-K programs serving tens of thousands of children, this creates universal early childhood for ages two through four.

This investment can provide free childcare that solves the affordability crisis. Or it can provide early childhood education that supports children's development while enabling parents to work with confidence that their child is safe, well cared for, and thriving with responsive educators. The difference is partnership infrastructure.

Partnership infrastructure is not about parent engagement in the abstract. It is about whether parents trust their child's program enough to focus on work. When parents do not trust the program, do not know what is happening during the day, cannot communicate concerns, or worry their child is not being seen and responded to, they cannot fully show up at work even though their child is in care. Partnership infrastructure serves both children's development and parents' ability to succeed because with two-year-olds, those things are inseparable.

When the city scaled pre-K and 3-K under former Mayor de Blasio, many family child care programs and small centers closed their doors (Kramer, 2026). The question now is whether 2-Care will be different. The answer depends on whether partnership infrastructure is budgeted for and built from the start, not added later when problems emerge.

Why Partnership Infrastructure Matters for Two-Year-Olds

Responsive care with two-year-olds depends on partnership infrastructure.

Two-year-olds are in a developmental period of rapid change. They're transitioning from infancy into early childhood. They're moving from primarily nonverbal communication to using words—most are using two-word phrases and by age three, some three-word phrases—but still rely heavily on adults reading their cues and understanding what they mean. They're testing boundaries and asserting "no" while still needing adults to help them navigate big emotions they can't yet regulate on their own. They're learning to use the toilet, feed themselves, and do things independently—but the timeline for these milestones varies widely across children and cultures. They're beginning to play interactively with peers rather than just alongside them, and you see an explosion in pretend play as they use their imaginations (ZERO TO THREE, n.d.). They're developing empathy and can comfort a peer who is hurt, while still struggling to resolve conflicts and share.

Parents of two-year-olds are often separating from their child for significant hours for the first time. They're wondering whether their child's development is typical when what counts as typical varies widely at this age. They're watching their child assert independence while worrying about whether educators will respond with patience or frustration. They're noticing cultural differences between how they were raised and what they see in early childhood programs—especially around toileting, feeding, discipline, and independence. They're making trust decisions about who to share concerns with and whether those concerns will be heard or judged.

For educators and administrators to meet families where they are and support two-year-olds, they need to understand what children are experiencing developmentally and what parents are navigating simultaneously. This requires infrastructure.

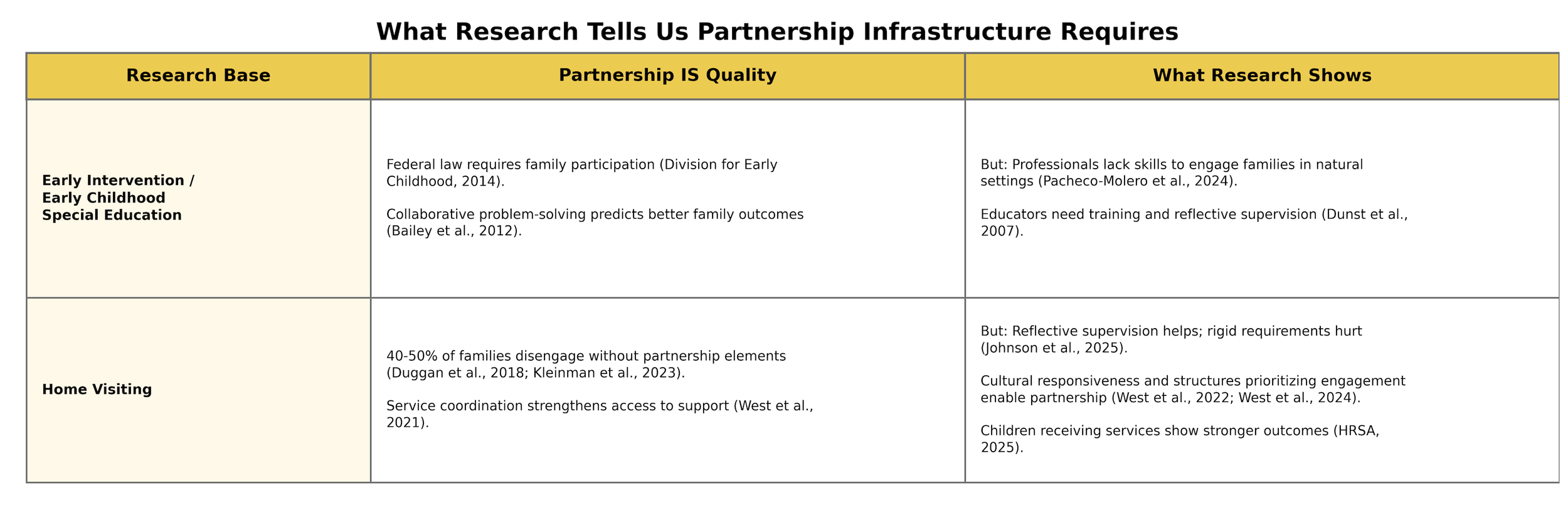

What Research Tells Us Partnership Infrastructure Requires

Research from early intervention, early childhood special education, and home visiting reveals what enables family-professional partnership to work.

Partnership practices produce positive outcomes. Meta-analyses examining family-centered practices in early intervention and early childhood special education show that families report higher satisfaction with services and stronger confidence in their parenting abilities. These approaches strengthen parent psychological well-being and parenting competence (Dunst, 2002; Dunst & Trivette, 2009). Children demonstrate better developmental outcomes, with positive effects on both parent-child interactions and child development across multiple domains (Trivette, Dunst, & Hamby, 2010). These findings led researchers to argue that family outcomes and family-centered services are central to program quality, not add-ons (Bailey, Raspa, & Fox, 2012). Critically, these benefits occur when educators provide information families can actually use to make decisions and when they work with families to set goals together rather than for them.

But partnership practices require infrastructure. The Division for Early Childhood's recommended practices (Division for Early Childhood, 2014) identify family-centered practices, family capacity-building practices, and family-professional collaboration as foundational to quality early intervention and early childhood special education. Research on these practices shows that educators need specific training and ongoing support to build relationships across cultural and linguistic differences, to engage in difficult conversations with families, and to recognize their own biases (Dunst, Trivette, & Hamby, 2007). A 2024 systematic review examining barriers to family-centered early intervention found that nearly half of studies identified professionals' lack of skills to engage primary caregivers in natural settings as a major obstacle (Pacheco-Molero et al., 2024). The research demonstrates that knowledge alone is insufficient—educators require structured opportunities to practice partnership skills, receive feedback, and reflect on how their own experiences shape their interactions with families. Many professionals report feeling insecure about their role when it shifts from being the expert working directly with children to coaching and supporting families. Without dedicated infrastructure for training, supervision, and organizational support, even well-intentioned educators default to more directive approaches because those are the responses their training and organizational systems have made most readily available.

What happens without partnership infrastructure. When home visiting programs fail to align with families' actual goals—meaning practitioners push predetermined curricula rather than responding to what families identify as important—when practitioners cannot respond flexibly to what families need because rigid program requirements prevent adaptation, or when working relationships remain weak because practitioners lack time and support to build trust, families leave. Research consistently shows that forty to fifty percent of families disengage from home visiting programs within the first year when these partnership elements are absent (Daro et al., 2012; Duggan et al., 2018; Kleinman et al., 2023).

What happens with partnership infrastructure. Reflective supervision—regular structured time with trained supervisors to examine practice, process emotional responses, and explore how practitioners' own experiences shape their work—helps practitioners navigate the emotional complexity of partnership work without burning out. A recent qualitative study examining contextual factors in home visiting practice found that reflective supervision and peer support help home visitors manage emotional demands and support well-being, while visit quotas and rigid fidelity requirements can clash with family realities and reduce engagement (Johnson et al., 2025). Training in cultural responsiveness strengthens capacity to work across difference by building skills in recognizing how cultural contexts shape parenting practices and family priorities. Organizational structures that prioritize engagement over service delivery metrics—measuring success by relationship quality and family-identified outcomes rather than visit counts or curriculum completion—create conditions where partnership becomes possible rather than an add-on (West, Madariaga, & Sparr, 2022; West, Spinosa, DeVoe, Madariaga, & Barnet, 2024). A recent federal study examining home visiting programs found that children whose families received home visiting services showed stronger social-emotional and behavioral outcomes by kindergarten entry (Health Resources and Services Administration, 2025).

What family-professional partnership research tells us:

Table comparing early intervention/ECSE and home visiting research on partnership infrastructure, showing that both fields demonstrate partnership requires training, reflective supervision, and organizational support to produce positive outcomes for families and children

Questions That Would Help Stakeholders Understand 2-Care's Partnership Infrastructure

As 2-Care moves into implementation, stakeholders across the early childhood field need to understand how partnership infrastructure is being built. These questions from EI/ECSE and home visiting research can help make that infrastructure visible:

From EI/ECSE models:

Will partnership be mandated or aspirational? Federal law requires family participation in assessment, planning, and decision-making processes in early intervention and early childhood special education. What accountability will 2-Care have for partnership?

Who coordinates partnership? Early intervention has service coordinators whose job is bridging families and services. Preschool special education does not—a gap parents recently identified as problematic (Gupta, 2026). Home visiting research demonstrates that service coordination strengthens families' access to support for maternal mental health, partner violence, and substance use concerns (West, Duggan, Gruss, & Minkovitz, 2021). Does 2-Care need a similar role, or will classroom teachers be expected to do this work without dedicated coordination?

From home visiting models:

Is reflective supervision funded? Home visiting programs budget for reflective supervision as essential infrastructure. Does 2-Care funding include this, or is it expected as an unfunded add-on that programs must somehow absorb?

What happens when families need affordable care to work? In home visiting, programs must create conditions that keep families engaged because families can leave. But 2-Care families need affordable care to work. They might stay enrolled even without strong partnership because they need the program. What supports families in voicing concerns when leaving is not a realistic option?

These questions can help all of us understand whether the billion-dollar investment in 2-Care includes the infrastructure that research shows family partnership requires.

Building Partnership Infrastructure Requires Investment

The research shows what family partnership requires. The challenge is that essential infrastructure often gets treated as optional—it seems like "just good practice" that should happen naturally. But partnership practices that seem like common sense still require concrete investments in six interconnected areas:

1. Time and structures for daily connection

Family-centered practices require treating families with dignity and respect, honoring their choices, and building on their strengths. Partnership builds through dedicated time for daily exchanges between educators and families.

Partnership requires ratios and schedules that allow for meaningful arrival and departure conversations, communication systems that work for families rather than assuming everyone reads email, and protected time in educator schedules for family communication that is valued as essential work rather than squeezed into margins. These structural changes have budget implications.

2. Professional development in partnership practices

Educators build partnership skills through specific training and ongoing support in building relationships across cultural and linguistic differences, engaging in conversations with families, and reflecting on how their own experiences shape their practice.

Training should address how to work with families on mutually agreed-upon goals, provide information families can actually use, and respond to families' actual reasons for participating. This training requires investment in educator capacity rather than one-time workshops.

3. Organizational policies that prioritize partnership

Partnership strengthens when policies frame families as partners rather than clients, create flexibility for work schedules and transportation constraints, and address power dynamics between families and staff. These policies support educators in relationship-building work, value partnership as much as curriculum implementation, and measure success by whether families experience true collaboration. Building these policies requires organizational structures and accountability systems that cost money to build.

4. Reflective supervision

Partnership work is emotionally complex. Practitioners build capacity through regular reflective supervision with trained supervisors to process their relationships with families, navigate challenges, and examine how their own experiences shape their practice. Home visiting programs budget for reflective supervision as essential infrastructure. Does 2-Care funding include this?

5. Cultural responsiveness as infrastructure

Strong working alliances require trust and rapport across cultural differences. Families decide whether to share concerns and communicate openly based on whether they experience cultural responsiveness in daily practice. Programs can build this through staff who reflect community demographics, interpretation and translation services for daily conversations rather than just crisis moments, ongoing educator learning about cultural practices around child-rearing, feeding, toileting, discipline, and family roles, and program practices that adapt to align with family cultures. This infrastructure requires budget allocations for intentional hiring, competitive compensation to attract diverse educators, and interpretation and translation services.

6. Systems for two-way communication

Family-professional collaboration requires reciprocal communication and shared decision-making. Families and educators build shared understanding through ongoing exchange about what they each see and what matters to them. Programs can build this through structured opportunities for educators to share observations about children's development and for families to share what they see at home, joint goal-setting processes that ensure families and educators work toward shared priorities, regular conferences focused on children's strengths and progress, clear pathways for families to voice concerns and ask questions, and processes for addressing conflicts when they arise. These systems require technology, staff time, and organizational commitment.

The Choice NYC Faces

NYC is investing one billion dollars per year in 2-Care. This investment is poised to solve affordability by providing free childcare. If structured intentionally, it can also provide early childhood education that supports children's development while enabling parents to work with confidence that their child is thriving. What makes both possible is partnership infrastructure.

Partnership infrastructure is not separate from program quality—it strengthens program quality. Without investment in this infrastructure, 2-Care will provide a place for children to be while parents work. With investment in partnership infrastructure, 2-Care can deliver on its promise of early childhood education that supports both children's development and parents' success. This matters especially when families need to trust programs with their children's safety.

The question is whether NYC will make the investment partnership infrastructure requires.

References

Bailey, D. B., Raspa, M., & Fox, L. C. (2012). What is the future of family outcomes and family-centered services? Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 31(4), 216-223. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271121411427077

Daro, D., Hart, B., Boller, K., & Bradley, M. C. (2012). Replicating home visiting programs with fidelity: Baseline data and preliminary findings. Mathematica Policy Research. http://communications.mathematica-mpr.com/publications/pdfs/earlychildhood/EBHV_brief3.pdf

Division for Early Childhood. (2014). DEC recommended practices in early intervention/early childhood special education 2014. https://www.dec-sped.org/dec-recommended-practices

Duggan, A., Portilla, X. A., Filene, J. H., Crowne, S. S., Hill, C. J., Lee, H., & Knox, V. (2018). Implementation of evidence-based early childhood home visiting: Results from the Mother and Infant Home Visiting Program Evaluation (OPRE Report 2018-76A). Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/opre/report/implementation-evidence-based-early-childhood-home-visiting-results-mother-and-infant

Dunst, C. J. (2002). Family-centered practices: Birth through high school. Journal of Special Education, 36(3), 139-147. https://doi.org/10.1177/00224669020360030101

Dunst, C. J., & Trivette, C. M. (2009). Meta-analytic structural equation modeling of the influences of family-centered care on parent and child psychological health. International Journal of Pediatrics, 2009, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2009/596840

Dunst, C. J., Trivette, C. M., & Hamby, D. W. (2007). Meta-analysis of family-centered helpgiving practices research. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 13(4), 370-378. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrdd.20176

Gupta, S. S. (2026). Practice architectures for NYC's early childhood expansion: What existing systems teach us about building infrastructure that serves children and families. Ecological Learning Partners LLC. https://ecologicallearningpartners.com/blog/practice-architectures-for-nycs-early-childhood-expansion

Health Resources and Services Administration. (2025). New HHS study finds home visiting services improves family wellbeing. https://www.hrsa.gov/about/news/press-releases/positive-home-visiting-by-kindergarten

Johnson, H. H., Eastern, A. C., Bragato, D., Joraanstad, A., & Filene, J. (2025). Voices from the field: Exploring contextual factors in home visiting practice. Home Visiting Applied Research Collaborative. https://hvresearch.org/

Kleinman, R., Ayoub, C., Del Grosso, P., Harding, J. F., Hsu, R., Gaither, M., Mondi-Rago, C., Kalb, M., O'Brien, J., Roberts, J., Rosen, E., & Rosengarten, M. (2023). Understanding family engagement in home visiting: Literature synthesis (OPRE Report No. 2023-004). Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/opre/hv_reach_literature_synthesis_dec2022.pdf

Kramer, A. (2026, January 8). Hochul plans to fund first 2 years of universal child care for NYC 2-year-olds. Chalkbeat New York. https://www.chalkbeat.org/newyork/2026/01/08/hochul-and-mamdani-announce-state-funding-for-nyc-2-care-universal-child-care

Pacheco-Molero, M., Morales-Murillo, C., León-Estrada, I., & Gutiérrez-Ortega, M. (2024). Barriers perceived by professionals in family-centered early intervention services: A systematic review of the current evidence. International Journal of Early Childhood, 57, 357–377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-024-00401-5

Trivette, C. M., Dunst, C. J., & Hamby, D. W. (2010). Influences of family-systems intervention practices on parent-child interactions and child development. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 30(1), 3-19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271121410364250

West, A., Duggan, A., Gruss, K., & Minkovitz, C. (2021). Service coordination to address maternal mental health, partner violence, and substance use: Findings from a national survey of home visiting programs. Prevention Science, 23, 478-489. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-021-01316-2

West, A., Madariaga, P., & Sparr, M. (2022). Reflective supervision: What we know and what we need to know to support and strengthen the home visiting workforce (OPRE Report No. 2022-101). Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.jbassoc.com/resource/reflective-supervision-what-we-know-and-what-we-need-to-know-to-support-and-strengthen-the-home-visiting-workforce/

West, A., Spinosa, C., DeVoe, M., Madariaga, P., & Barnet, B. (2024). Implementation of training and coaching to improve goal planning and family engagement in early childhood home visiting. Children and Youth Services Review, 159, 107466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2024.107466

ZERO TO THREE. (n.d.). 24 to 36 months. https://www.zerotothree.org/resources/for-families/24-to-36-months/

Sarika S. Gupta, Ph.D. | Founder, Ecological Learning Partners LLC | Learning Architect