UDL as Essential Infrastructure: Designing Practice Architectures Beyond Verbal Fluency

Some of us think best when we have time to write our way into understanding.

But in most educational systems and professional spaces, verbal fluency functions as a gate. Tenure-track interviews, for example, require a full day of meetings with deans, faculty, and doctoral students. Candidates present research, teach a demonstration class, and navigate meals and hallway conversations. This demands eight to ten hours of continuous verbal performance with no processing time between sessions.

Conference presentations include real-time Q&A with little to no processing time. Deans assess faculty participation through speaking up in the moment. Hiring processes measure competence through quick verbal response. Professional development sessions expect immediate verbal engagement. Dissertation defenses require spontaneous answers to complex questions (though a good dissertation chair will help you prepare for possible questions). Committee work values those who can articulate positions without preparation.

What happens to the knowledge that only becomes visible through slower, messier, more embodied processes?

I know this gate intimately.

Looking back at my middle school, high school, and college education, I see now what felt ordinary then: teachers who created space for different ways of thinking and learning.

In middle school, our librarian taught us to research using notecards. We wrote one fact per card, source and page number on the back. Then we laid them all out and moved them around until we built the structure for our paper. I was writing biographies of Mahatma Gandhi and Winnie Mandela - Gandhi was required, Mandela was my choice. I loved spreading those cards across the floor, seeing patterns emerge as I arranged and rearranged. I was tetrising what I'd read to make the content manageable, breaking complexity into pieces I could physically move. With the facts laid out, we could start to tell the story - weave it together with openers, transition sentences, and then draw our conclusions through our interpretation, our lens. We had to trust the data and what we thought. She created space for spatial organization and mapping.

In 8th grade, our English teacher encouraged us to sketch poetry - visual form, spatial relationships on the page - and to turn in these sketches with our final work (two poems were later published at her encouragement). She created space for visual and embodied expression.

In 11th grade AP English, reflective journals were required for class. They physically felt good to write and review. I used one of those reflections as my college essay because I trusted the thinking-on-the-page. He had created space for sustained reflection and processing.

By 12th grade, I found myself pleasantly losing myself in flow states writing our final research paper in psychology class - extracting information from multiple sources, piecing it together, refining the message through the mess. My teacher encouraged me to choose a topic I could immerse myself in. I was applying all of these learnings - the spatial organization from middle school notecards, the visual thinking from sketched poetry, the reflective processing from daily journals, the synthesis work of weaving multiple sources together.

These teachers weren't naming their work as UDL. But looking back, each one built upon what came before, creating space for multiple pathways to understanding.

In college, I had a children's literature professor who, after we read a children's book about the magic and meaning of a quilt, encouraged us to create a quilt naming the influences in our lives. She probably expected us to sketch this on paper, which is what most students did. But I went to fabric stores and actually made a quilt - piecing together fabric squares that represented different influences in my life. I still have that quilt. I'm proud of it - not just as an object, but for what creating it revealed about how I learn. I needed to work spatially, to piece things together physically, to see patterns emerge through my hands. I was becoming the kind of teacher I hoped to be.

But these spaces - where teachers designed for multiple modalities, where embodied and spatial thinking were valued alongside verbal fluency - became increasingly rare as I moved through higher education and into professional academic spaces, particularly on the tenure track.

Verbal fluency demands the opposite. It requires knowing your conclusion before you speak, articulating clearly in real-time, demonstrating competence through immediate response. There is no space for the processing step where my thinking actually happens. And I need space to sit with the thinking and movement to think.

What I Noticed in Professional Preparation: Verbal Fluency as a Gate

Over the course of my career, I have worked with teachers in early childhood special education and inclusion spaces. I prepare them for this work and invite them to reflect on their practice. This is a field that teaches Universal Design for Learning, that prepares educators to recognize learners access knowledge through multiple pathways, that values individualization and differentiation.

But I kept noticing the same pattern. The invisible infrastructure of professional participation - in teacher preparation programs, in professional development sessions, in school-based collaboration - consistently privileges one pathway: real-time verbal fluency.

I have spent my career navigating this tension, often feeling isolated in professional spaces that do not make room for the way I know.

We teach UDL for curriculum delivery. We need to apply it to how we design practice architectures for professional participation.

What Is Universal Design for Learning?

Universal Design for Learning is a framework developed by CAST that recognizes learners differ in how they perceive information, express what they know, and engage with learning. The UDL Guidelines provide a framework for creating learning experiences with:

Multiple means of engagement (the "why" of learning - how learners get motivated and sustain effort)

Multiple means of representation (the "what" of learning - how information is presented and perceived)

Multiple means of action and expression (the "how" of learning - how learners demonstrate what they know)

We teach this framework to prepare educators for diverse classrooms. We need to apply these same principles to how we structure professional participation for teachers, teacher educators, and educational researchers.

Designing practice architectures for professional learning requires UDL.

What Stays Invisible in Current Structures?

Research on teacher learning reveals important insights about how teachers make sense of professional development. Marshall and Horn (2025) found that teachers engage in what they call "agentic synthesis" when they take practices from professional development and adapt them to their classroom contexts. This synthesis work requires teachers to integrate new practices with their existing knowledge, their specific student populations, their school contexts, and their professional identities. This is not a quick process of implementation. It is a complex process of sense-making that unfolds over time and across contexts.

Yet most professional development structures assume teachers can immediately articulate their understanding and application plans in real-time discussion. The processing step - where teachers actually synthesize new practices with their existing knowledge and context - often happens invisibly, in the spaces between formal professional learning sessions.

Research on embodied and multimodal inquiry points to what gets lost when we rely solely on language-based data collection and sharing. Rieger et al. (2022) argue that when researchers collect embodied and multisensorial data but then translate everything into language for analysis and presentation, the embodied and relational aspects of that knowledge often disappear. The same pattern occurs in professional learning contexts. When we structure teacher reflection and collaboration to privilege verbal articulation, we lose access to the embodied, spatial, and temporal ways many teachers process their practice.

Similarly, research on self-study in teacher education emphasizes the importance of teachers developing awareness of themselves as practitioners. Pithouse-Morgan (2022) found that self-study researchers recognize they must understand themselves as teaching and teacher education practitioners in order to grow in their field. This self-awareness develops through sustained reflection that often requires multiple modalities - writing, mapping, collaboration, time for processing - not just immediate verbal articulation in group settings.

Designing professional learning structures must make space for this synthesis work, this embodied knowing, this development of practitioner self-awareness. UDL provides the framework for building these practice architectures.

Designing Practice Architectures with UDL

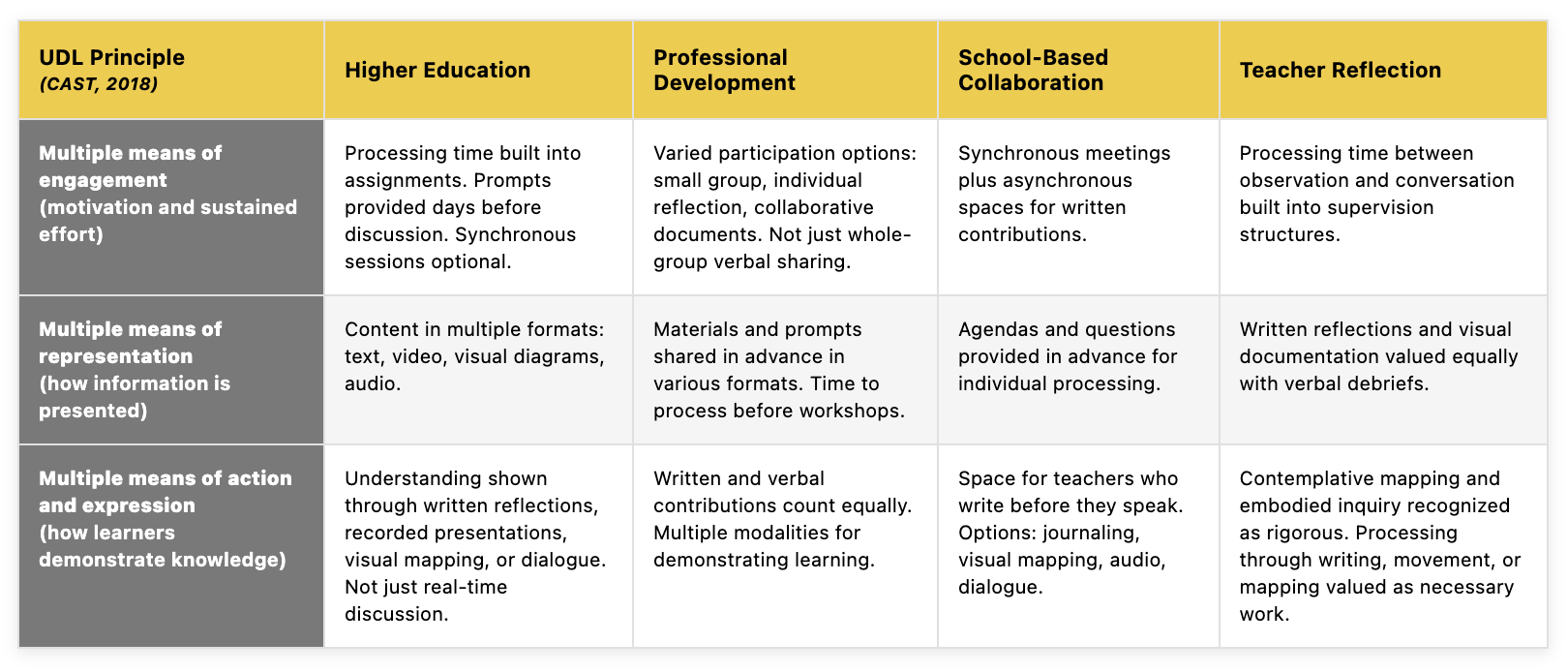

The table below shows how UDL principles can be integrated into practice architectures for professional participation in early intervention, early childhood, special education, and early childhood education contexts.

This table presents Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles and their applications across four professional contexts. The table has five columns and four rows. The first column lists three UDL principles (engagement, representation, and action/expression). The remaining four columns (Higher Education, Professional Development, School-Based Collaboration, and Teacher Reflection) provide specific examples of how each principle can be implemented in each context.

What Does UDL-Informed Design Reveal?

In my university teaching positions - both tenure-track and clinical line - I taught 17 courses over 6 years. Seven of those courses were taught in various online formats: hybrid, asynchronous, synchronous.

In some settings, I had full responsibility and was entrusted to design the courses. This trust was itself part of the practice architecture - being given the autonomy to apply UDL principles I knew from my special education background. When I didn't know the technical features of online teaching, support was available. At George Mason University, online learning staff provided training in the technical aspects. At George Washington University, colleagues graciously shared their expertise, course materials, and resources to help me design courses. I could learn what I didn't know.

In contrast, in one setting the course structure was predetermined with no opportunity for instructor input or adaptation.

When I entered another graduate program - fully online - I was nervous about how courses would be structured. Would I have the space to process and learn in the ways my thinking requires?

This semester, in my data science program, I opened a course syllabus and the tension in my body deflated immediately.

The course is fully asynchronous with optional synchronous sessions. All activities that happen during live class sessions are also posted to the learning management system. These activities are optional, sometimes worth extra credit, but never required. The instructor records all sessions for those who cannot or choose not to attend live. Primary collaboration happens via text-based channels. Processing time is built into every assignment.

The instructor wrote this in the syllabus: "Since the class is asynchronous, you are not required to attend live sessions. I'll record the meetups, and any 'in class' activity will be posted and are optional."

This is not accommodation. This is design.

It works for the busy professional. It works for the neurodivergent learner. It works for the person who thinks best through writing. It works for multiple pathways without requiring anyone to disclose why they need it.

Not all course content can be fully asynchronous. Instructors need information about student learning to provide useful feedback. Students need opportunities for formative learning - not just summative assessment - where they can develop understanding through interaction and revision. Some content benefits from real-time collaboration. But UDL principles don't require everything to be asynchronous. Research on UDL as a framework in professional nursing preparation demonstrates that intentional design can meet the needs of diverse learners across professional preparation contexts - including early intervention, early childhood special education, and teacher education. Systematic reviews of UDL in online education show this requires specific design choices: providing discussion questions in advance so students can process before synchronous sessions, offering multiple ways to demonstrate understanding (written response, recorded video, visual diagram), building processing time between instruction and assessment, making synchronous sessions optional when the same learning can happen asynchronously, giving learners agency to choose how they engage while maintaining accountability for learning. The question is whether we build structures that support different ways of learning and thinking, or whether we default to privileging only one.

My body knew before my mind did that this is a space where my thinking can breathe.

Making Invisible Infrastructure Visible

These experiences - from my teachers who created space for multiple pathways, to the institutional colleagues and resources who supported my course design in higher education settings, to this data science course designed with UDL principles - illustrate what becomes possible when we design practice architectures intentionally rather than defaulting to structures that privilege verbal fluency. My teachers knew how to do this without naming it UDL. But recognizing these patterns and designing them intentionally into higher education and professional learning contexts requires methodologies that help us see the invisible infrastructure - the assumptions about how thinking happens, whose ways of knowing count as rigorous, what participation looks like.

I use contemplative mapping methodology in my work with Ecological Learning Partners. Contemplative mapping encompasses approaches like practice mapping, life mapping (forthcoming), and situational mapping that help make embodied knowledge and relational infrastructure visible. The methodology builds on early childhood educators' existing observation and documentation practices, extending them to examine our own practices and the systems we work within. Contemplative mapping enables the processing that knowing requires - the time to sit with complexity, the space to examine messiness, the movement to map connections that don't follow linear logic.

This processing is not inefficiency. It's where knowing happens.

References

CAST. (2018). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 2.2. http://udlguidelines.cast.org

Coffman, S., & Draper, C. (2022). Universal design for learning in higher education: A concept analysis. Teaching and Learning in Nursing, 17(1), 36-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.teln.2021.07.009

Marshall, S. A., & Horn, I. S. (2025). Teachers as agentic synthesizers: Recontextualizing personally meaningful practices from professional development. Journal of the Learning Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2025.2468230

Pithouse-Morgan, K. (2022). Self-study in teaching and teacher education: Characteristics and contributions. Teaching and Teacher Education, 119, 103880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2022.103880

Rieger, J., Devlieger, P., Van Assche, K., & Strickfaden, M. (2022). Doing embodied mapping/s: Becoming-with in qualitative inquiry. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 21, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069221137490

Yang, M., Duha, M. S. U., Kirsch, B. A., Glaser, N., Crompton, H., & Luo, T. (2024). Universal design in online education: A systematic review. Distance Education, 45(1), 23-59. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2024.2303494

Sarika S. Gupta, Ph.D. | Founder, Ecological Learning Partners LLC | Learning Architect