What's Emerging at the Edges: An Inquiry Into Early Childhood Education Practice Architectures

An inquiry into the practice architectures shaping teacher knowing across traditional and nontraditional learning environments

Why I'm Looking at the Edges

I've been thinking about something that keeps surfacing in conversations with teachers, families, and colleagues: what if we're designing early childhood systems from the wrong starting point?

My professional aim has always been about personalized learning—for children, families, AND teachers. By personalized, I don't mean individualized curriculum. I mean responsive to who people are and what they need to thrive. Recent research on flexible learning options asks important questions about access and equity in a growing ecosystem of choices. But I'm wondering about the practice architectures underneath: what arrangements make personalized learning possible in the first place?

Universal design teaches us that designing for the margins often reveals better solutions for everyone. The curb cut is the classic example: designed for wheelchairs, now used by parents with strollers, travelers with luggage, delivery workers with carts. Though anyone who's navigated NYC sidewalks knows the implementation doesn't always live up to the principle—curb cuts can be bumpy, water-pooled, sometimes more obstacle than access. But the principle holds: when we design from the margins, benefits cascade outward. What if we applied that thinking to early childhood systems themselves?

The traditional approach designs for the mainstream and then tries to accommodate everyone else. But what if we looked at what's happening at the edges—the microschools, the pods, the hybrid models—as spaces revealing what's possible when we design from the margins inward? This isn't about advocating for any particular model. It's about understanding what the margins teach us about conditions that enable teacher knowing and family agency.

I'm getting the lay of the land right now, mapping what's emerging and what it might reveal about practice architectures that matter everywhere. This is thinking in progress.

What's Shifting

Something is shifting in early childhood education, and we're seeing it most clearly where traditional structures are loosening. Teachers are leaving center-based programs not because they don't care about young children, but because the conditions make it impossible to do the work they know matters. At the same time, families are creating learning pods, microschools are emerging in living rooms and community spaces, and hybrid models are reimagining when and where learning happens.

Instead of asking "what's wrong with traditional early childhood education" or "are these alternatives good or bad," I'm curious about: What are we learning about the conditions that enable teacher knowing and learning across these different contexts?

This question matters because it shifts us from evaluating models to understanding practice architectures—the arrangements of sayings, doings, and relatings that make certain kinds of teaching and learning possible or impossible in any given context.

Making the Invisible Visible: What Practice Architectures Reveal

Practice architectures theory helps us see how three dimensions shape what's possible for teachers:

Cultural-discursive arrangements: What language is available to describe teaching work? What counts as "professional development"? Whose knowledge is recognized?

Material-economic arrangements: What physical spaces exist? What resources flow where? What compensation enables sustainability?

Social-political arrangements: Who decides what quality looks like? Where does power concentrate? What relationships are supported?

In traditional center-based early childhood programs, we're seeing a particular set of arrangements that has created both deep expertise AND unsustainable conditions:

Median wages of $13.07/hour despite increasing credential requirements

30% annual turnover even in well-resourced programs

14% of Head Start classrooms closed due to staffing shortages

What's emerging in nontraditional spaces offers not solutions but different arrangements to study—new combinations of conditions that make different kinds of knowing and learning possible.

What's Being Learned in Emerging Spaces

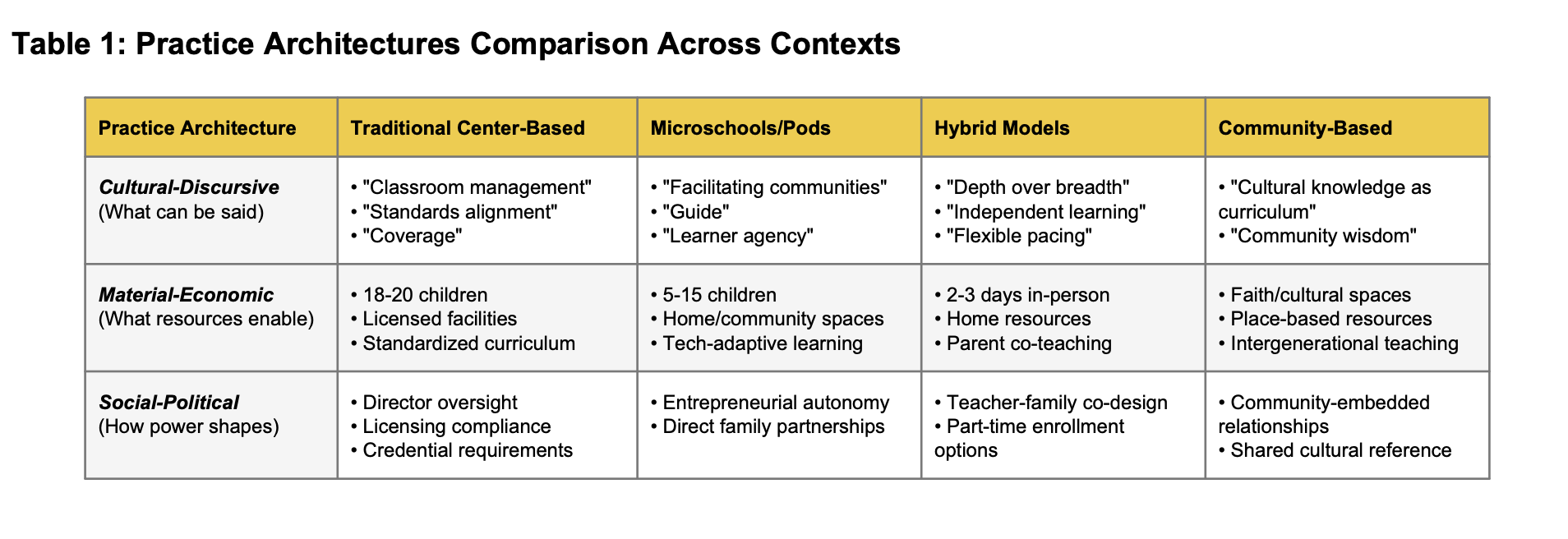

The practice architectures shift differently across contexts. Here's what we're noticing:

A comparison table showing how practice architectures—cultural-discursive sayings, material-economic resources, and social-political power structures—differ across traditional center-based, microschool/pod, hybrid, and community-based early childhood settings.

Each of these arrangements creates different possibilities for what teachers can come to know:

Microschools and Learning Pods: Practicing at Human Scale

Small-scale learning environments (typically 5-15 children) are revealing something about the relationship between scale and teacher knowing. When a teacher works with 8 children instead of 18-20, what becomes possible to know about each child? These aren't inherently better arrangements—they create different possibilities and different constraints. A microschool teacher might have more autonomy in curriculum decisions but less access to specialized support for children with complex needs.

What we're noticing: When educators have more direct control over their practice architectures, they report staying in the field longer. The question becomes: what enables this agency, and who gets access to it?

Hybrid Models: Reimagining When/Where Learning Happens

Hybrid homeschool programs are revealing assumptions about the temporal and spatial containers we've built for learning. When children learn in-person 2-3 days per week and work independently or with families the rest of the time, what does this reveal about teacher knowing?

What we're noticing: Part-time enrollment is becoming policy in some states, suggesting these temporal arrangements might be compatible with public education infrastructure. The question becomes: how do we support teacher learning when the rhythm of practice changes?

Community-Based Models: Practicing in Cultural Context

Faith-based programs, culturally-specific learning environments, and neighborhood-rooted initiatives are revealing how context shapes what's knowable. When teaching happens within rather than separate from community, what becomes visible that was previously invisible?

What we're noticing: These spaces often resist professionalization pressures in ways that preserve cultural knowledge while also limiting access to resources and support structures. The question becomes: how do we support community-based teacher learning without imposing homogenizing "quality" frameworks?

The Gaps We're Seeing in Early Intervention/Early Childhood Special Education

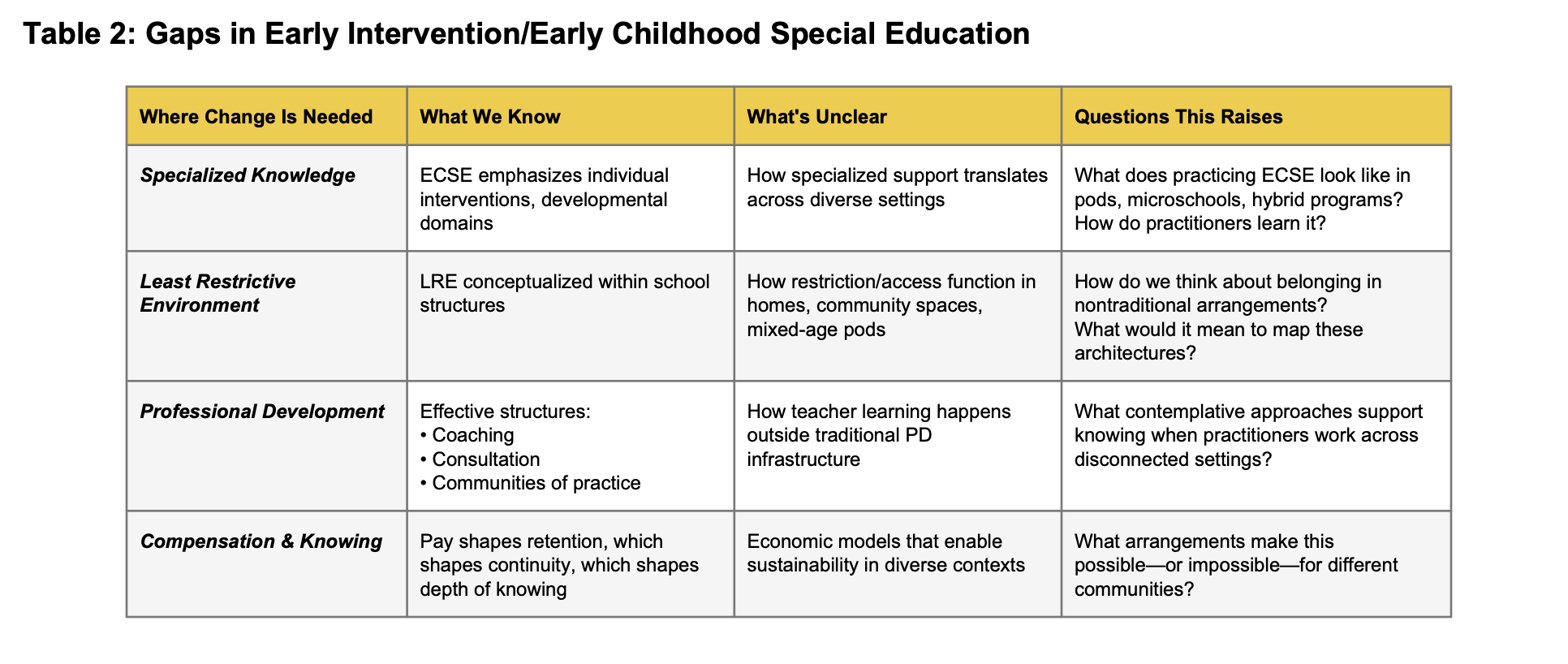

This exploration reveals particular tensions in EI/ECSE where change feels necessary but unclear:

A table identifying gaps in early intervention and early childhood special education across four areas—specialized knowledge, least restrictive environment, professional development, and compensation—by contrasting what we know, what remains unclear, and questions this raises for practice.

1. Where Specialized Knowledge Lives

Traditional ECSE preparation emphasizes individual interventions and developmental domains. But emerging research on inclusive practice suggests we need teachers who can read relational patterns, design flexible environments, and collaborate with families as co-designers. We haven't yet mapped what practicing ECSE looks like outside traditional program structures.

2. How We Understand "Least Restrictive Environment"

Least Restrictive Environment (34 C.F.R. § 300.114-300.120) was conceptualized within traditional school structures. Our regulatory language doesn't yet have ways to name the practice architectures that enable belonging in nontraditional spaces.

3. What Counts as Professional Development

Professional development research has identified effective structures like coaching, consultation, and communities of practice. But these assume particular organizational arrangements. Teachers in nontraditional settings report learning through peer networks, self-directed study, and practice-embedded inquiry.

4. How Compensation Connects to Knowing

Research consistently shows that compensation shapes retention, which shapes continuity, which shapes what teachers can come to know about children over time. But some microschool models pay teachers 25% more while serving similar populations. We haven't mapped the economic arrangements that make this possible—or impossible.

Moving Toward Inquiry Rather Than Evaluation

The field is grappling with questions about whether these alternative models serve all children equitably, whether they maintain quality, whether they fragment an already fragile system.

These are important questions. But I'm wondering if we need different questions first:

Rather than:

“Are microschools/pods/hybrid models good or bad?"

We might ask:

“What practice architectures enable teacher knowing and learning in alternative contexts?”

“What makes certain kinds of observation possible?”

“What enables sustained attention to each child?”

Rather than:

"Do alternative models meet quality standards?"

We might ask:

“What do quality standards assume about the arrangements of teaching practice?”

“What becomes invisible when we apply standards developed in one context to practices happening in another?”

Rather than:

"How do we regulate these spaces?"

We might ask:

“What are we trying to make visible through regulation?”

“What relational infrastructure actually supports children's thriving, and how do we help practitioners develop the capacity to observe and strengthen it?”

What This Means for Early Intervention/Early Childhood Special Education

If we take seriously the idea that teacher knowing matters more than program model, several implications emerge:

1. We need contemplative approaches to professional learning across contexts

Not standardized training that assumes everyone practices in similar arrangements, but methodologies that help practitioners develop discriminative awareness—the capacity to observe the specific practice architectures shaping their work and make intentional choices within them.

2. We need to make economic arrangements visible

Compensation data shows the material conditions of teaching are themselves a teaching about what society values. Making these arrangements visible—mapping who earns what, where money flows, what economic models exist—is part of understanding what's possible.

3. We need language for relational infrastructure

What enables teachers to maintain connection with children, families, and each other over time? What creates the conditions for the kind of knowing that develops slowly through sustained observation? These questions require mapping relational networks not just evaluating structural features.

4. We need to attend to who gets to innovate

The emerging spaces aren't equally accessible. Some families can form learning pods; others cannot. Some teachers can become microschool entrepreneurs; others face barriers. Making these patterns visible is essential work.

Holding the Complexity

Parents want choices that work best for their child and family. That's not a problem to solve—it's a reality to design for.

This isn't an argument for or against any particular model. Traditional center-based programs have developed crucial expertise in supporting diverse learners. Public pre-K programs serve children whose families might not access alternatives. The infrastructure matters deeply.

At the same time, what's emerging at the margins is teaching us something. When we look at the practice architectures in these spaces without immediately evaluating them, we can ask:

What becomes possible to know about children when arrangements shift?

What kinds of teacher learning happen in different conditions?

What relational infrastructure supports sustained attention and care?

What economic arrangements make it possible for teachers to stay and deepen their knowing?

These questions matter whether we're working in traditional programs or emerging alternatives—because they help us see what we might be missing about the invisible infrastructure that enables thriving.

Questions for Further Mapping

This margin-to-center thinking raises questions I'm continuing to explore:

What practice architectures enable teacher knowing? What sayings, doings, and relatings make it possible for teachers to really see and respond to children over time? How do these arrangements differ across contexts, and what can each context learn from the others?

How do we study knowing across diverse contexts? Traditional evaluation assumes certain arrangements as standard. What would we see if we mapped relational infrastructure instead—the actual conditions that support sustained observation and responsive practice?

What does "design from the margins" mean for policy? Rather than asking "how do we regulate these spaces," what if we asked "what conditions enable teachers to develop and maintain the capacity to observe, know, and respond—and how do we support those conditions across all contexts"?

Where do families see it? What do parents notice about the arrangements that help teachers really know their child? What matters most about structure versus relationship versus resource versus time?

The field is in disarray, yes. But disarray creates openings. What we're seeing at the margins isn't a replacement for traditional early childhood education—it's revealing conditions that enable teacher knowing and family agency.

What if we designed systems with those conditions as the starting point?

____________________________________________________

References

Bellwether Education Partners. (2024). Research agenda: Expanding equitable access to flexible personalized education. https://bellwether.org/publications/research-agenda/

Blackwell, A. G. (2017). The curb-cut effect. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 15(1), 28-33. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/the_curb_cut_effect

Bryant, D., & Yazejian, N. (2023). Retention and turnover of teaching staff in a high-quality early childhood network. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 65. https://fpg.unc.edu/news/investigating-teaching-staff-turnover-early-childhood-education

Center for the Study of Child Care Employment. (2024). Early childhood workforce index 2024. University of California, Berkeley. https://cscce.berkeley.edu/workforce-index-2024/

Changemaker Education. (n.d.). The different types of microschools: Finding the right fit for your child. https://www.changemakereducation.com/post/the-different-types-of-microschools-finding-the-right-fit-for-your-child

EdSource. (2024, August 23). The rise of microschools: A wake-up call for public education. https://edsource.org/2024/the-rise-of-microschools-a-wake-up-call-for-public-education/717798

Floresca, F. (2023, April 18). Microschools and learning pods: A movement of education innovation. America's Future. https://americasfuture.org/microschools-and-learning-pods-a-movement-of-education-innovation/

Fodness, E. (2024). Exploring the current landscape of the United States early childhood care and education workforce. Early Childhood Education Journal. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10643-024-01730-9

Gupta, S. S., & Nagasawa, M. (2023). WeDesign: Conceptualizing a process that invites young children to codesign inclusive learning spaces. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/14639491231179000

Hognestad, K., & Bøe, M. (2017). The practice architectures of middle leading in early childhood education. International Journal of Child Care and Education Policy, 11(8). https://ijccep.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40723-017-0032-z

Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act, 34 C.F.R. § 300.114-300.120 (2006). https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-34/subtitle-B/chapter-III/part-300/subpart-B/subject-group-ECFR6f294ba652a5e6b

Learning Policy Institute. (n.d.). Teacher recruitment, retention, and shortages. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/topic/teacher-recruitment-retention-and-shortages

McShane, M. Q. (2024). A new crop of school models expands choice: Families find more-personal alternatives in microschools, hybrid homeschools. Education Next, 24(2). https://www.educationnext.org/a-new-crop-of-school-models-expands-choice-alternatives-microschools-hybrid-homeschools/

Navigate School Choice. (n.d.). The ultimate guide to microschooling and mix-and-match learning. https://myschoolchoice.com/types-of-schools/micro-schools

Northgate Academy. (2022, October 27). What are micro-schools & homeschool pods? https://www.northgateacademy.com/blog/what-are-micro-schools-homeschool-pods/

OpenEd. (n.d.). A beginner's guide to microschools: The educational trend growing faster than homeschooling. https://opened.co/blog/a-beginners-guide-to-microschools-the-educational-trend-growing-faster-than-homeschooling

Practice Architectures ECE. (n.d.). The theory of practice architectures in early childhood education. https://practice-architectures-ece.com/

Renegade Educator. (2023, March 27). 11 alternative school models we love: Which one is right for your kid? https://renegadeeducator.com/alternative-education-models/

Sheridan, S. M., Edwards, C. P., Marvin, C. A., & Knoche, L. L. (2009). Professional development in early childhood programs: Process issues and research needs. Early Education and Development, 20(3), 377-401. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2756772/

Teaching Strategies. (2024). The impact of teacher turnover on child development and learning. https://teachingstrategies.com/blog/the-impact-of-teacher-turnover-on-child-development-and-learning/

TSH Anywhere. (2024, October 7). Pandemic pods and microschools: Find or start near you. https://www.tshanywhere.org/post/pandemic-learning-pods-microschools

This exploration examines practice architectures shaping early childhood teaching across contexts, drawing on workforce research, documentation of emerging models, and professional development research. It's written from my lens and experiences as a classroom teacher, instructional coach, technical assistance provider, university faculty, and researcher in early childhood systems.