Life Mapping My Faculty Experience

When the Tenure Track Felt Like a Jail

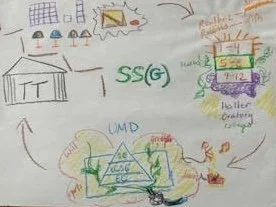

In the Spring of 2022, our research team was building reliability for the life map prompt we would use with PreK teachers. When I drew my own map—the first one—I drew the tenure track as an institutional jail. Stark black and white. Vertical pillars. A literal cage.

The image revealed something I hadn't been able to articulate: the ecology of institutions of higher education (IHEs) wasn't a good fit for me. And I had made myself endure it for a decade.

The feelings it brought up—shame, embarrassment, unease—were so uncomfortable that I drew a second map to share with teachers during interviews. One that looked more coherent. More like what a successful researcher's journey should look like.

The Methodology That Made the Invisible Visible

This revelation emerged through life mapping, a qualitative research method we were using in our study examining preschool inclusion in New York City. The approach, inspired by Futch and Fine's (2014) work on mapping as method and Beneke's (2021) research on teacher candidates' educational trajectories, invites participants to visually represent their educational journeys—including people, places, obstacles, and opportunities along the way.

The prompt is deceptively simple: Map your journey. Use colors for different feelings. Include what felt comfortable and what didn't.

But what emerges is rarely simple.

Two Maps, Two Different Truths

The first map I drew—the one I couldn't share with teachers—made visible what I had been unable to name. The tenure track – as a structure with bars. Black and white. No color, no flow. An institutional cage.

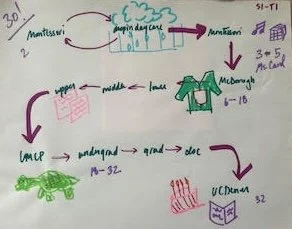

The second map presents a more conventional narrative of my educational journey - an occasional daycare I hated, a nurturing Montessori program, 1st to 12th grade at a private school with a uniform, and then the University of Maryland, my professional home where I earned my bachelors, master, and doctorate before moving on to my postdoc out west. This second map was organized, purposeful, and showed growth.

But I didn't sit with the first map long enough to understand what it was telling me.

I'm now recognizing, nearly three years later, that I intuitively knew the ecology of IHEs wasn't right for me when my daughter was born in 2021. I knew it when I took my grant funding from a tenure-track position to Bank Street College—a place where I hoped I could be both supportive and thrive, even though I had hoped I would be supported to thrive on the tenure track.

My hands drew what I couldn't yet articulate.

The Gap Between Method and Practice

Our research study asked PreK teachers to share their vulnerabilities—their educational journeys, moments of discomfort, experiences that shaped their beliefs about which children belong in their classrooms. We invited them to create life maps showing where they felt included and where they didn't.

I was asking them to do something I couldn't do myself.

When the moment came to create my own map, I drew the jail. Then I drew something else to share with teachers. Something that wouldn't expose the misalignment between who I was and the institution I represented.

Futch and Fine (2014) describe mapping as a "mediational method"—it doesn't just collect data, it confronts us. In my case, it confronted me with a fundamental research ethics question: How can we ask participants to be vulnerable when we're unwilling to engage our own vulnerability as researchers?

Sitting With Data—Including Your Own

Contemplative research practice emphasizes staying with what emerges without rushing to interpretation. Not explaining away discomfort. Letting what is uncomfortable remain uncomfortable. In other words, "sitting with data."

I didn't sit with my first map. I drew it, felt the discomfort, and immediately created a replacement. This is what Beneke (2021) describes in her work on teacher candidates: we avoid the data that implicates us in the systems we critique.

Nearly three years later, the unease remains. But it has shifted from shame about drawing a jail to recognition that the confinement was real. My daughter's birth in 2021 created the conditions for recognizing what the first map revealed: I could choose differently. I could take my grant elsewhere and build from there, even as I initially told myself I would stay on the tenure track. My body knew before my mind could admit it—the jail wasn't just a metaphor I'd drawn, it was a reality I needed to leave. The map had shown me the truth in January 2022; it would take nearly two more years to stop explaining it away.

Taking my grant funding to Bank Street College was not, as I initially framed it, a strategic move to stay in the tenure-track game. It was following what my hands had already drawn—finding a way out. This embodied inquiry—the body knowing before the mind can articulate—would become essential as I navigated the space between institutional identities.

What the Maps Reveal About Method and Researcher Positionality

Looking at both maps nearly three years later, I see layered meanings:

The institutional structure I drew was accurate. The confinement felt and was real.

But I was also so socialized into academic performance that even in a research study designed to make invisible systems visible, I made my own experience invisible. I chose the version that looked like success.

This raises methodological questions about researcher positionality. Beneke's work examining how teacher candidates appropriate meanings about normalcy through socio-spatial school processes applies to researchers too. We move through institutional spaces that shape what we can see and say about ourselves.

The map made visible what I wasn't ready to name. Now, three years into sitting with this data, I can see both the revelation and my initial response to it as part of the same ecology—one that centers certain ways of being a scholar while constraining others.

The insights shared here are emerging from our NYC preschool inclusion study, which launched in January 2022. You can read more about the study in our recent Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood publication.

References:

Gupta, S.S., Cheatham, G.A., Strassfeld, N., Zhu, X., Medellin, C., & Nagasawa, M. (2024). Examining the ecology of preschool inclusion in New York City: A mixed-methods study underway. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood. https://doi.org/10.1177/14639491241229229

Sarika S. Gupta, Ph.D., is the founder of Ecological Learning Partners LLC.