The Data That Waited: What 272 Teachers Taught Me About Invisible Networks

A journey from documenting teacher wellbeing to contemplative mapping

The Study That Captured a Moment

In 2019, I published an article in Young Exceptional Children arguing that teacher wellbeing matters for inclusive practice. The premise was straightforward: when educators are pushed to their emotional limits without support, it affects their capacity to provide the responsive care young children need.

I wasn’t satisfied with making the argument. I had lived it, certainly, but I wanted evidence beyond my own experience.

That same year, I launched what I had intended to be a multi-year, mixed-methods research program on teacher wellbeing in inclusive preschool settings. I was awarded a PSC-CUNY Research Award. I designed a comprehensive survey using validated instruments specifically chosen for rigor: the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), the Subjective Happiness Scale, and the Early Childhood Job Satisfaction Survey (ECJSS). I secured IRB approval. I built recruitment partnerships with early childhood program leaders and recruited teachers mostly across the Mid-Atlantic region and in the South through systematic snowball sampling.

The response was significant. A total of 272 teachers participated—nearly all (92%) were lead teachers in center-based settings. Their classrooms served 3-5 year olds. And crucially, 91% taught at least one child with an IEP or IFSP. These weren’t teachers dabbling in inclusion—they were doing the daily work of creating classrooms where all children belonged.

This was phase one of a larger agenda: establish baseline data, conduct follow-up interviews, develop interventions, and inform policy. I presented preliminary findings at the 2020 CRIEI conference and was scheduled to present at AERA that spring. The work was gaining traction—then the pandemic arrived.

Data collection stretched into 2021. Career transitions followed—not of my choosing—along with becoming a parent and navigating educational systems from the other side. The comprehensive analysis, the qualitative interviews, the intervention development—all remained undone. The research program got interrupted before reaching its potential.

What the Numbers Held

I returned to the data this fall, five years later. Not to run the sophisticated models I'd originally envisioned—I no longer have access to individual-level responses—but to listen to what 272 teachers reported collectively.

Before diving in, context matters: 71% identified as White, 84% worked in Head Start programs, concentrated in the mid-Atlantic. This was phase one—I'd planned to expand recruitment to capture more diverse experiences across race, program type, and geography. That expansion never happened, which means these findings reflect a particular slice of the inclusive preschool teacher workforce, not the full picture.

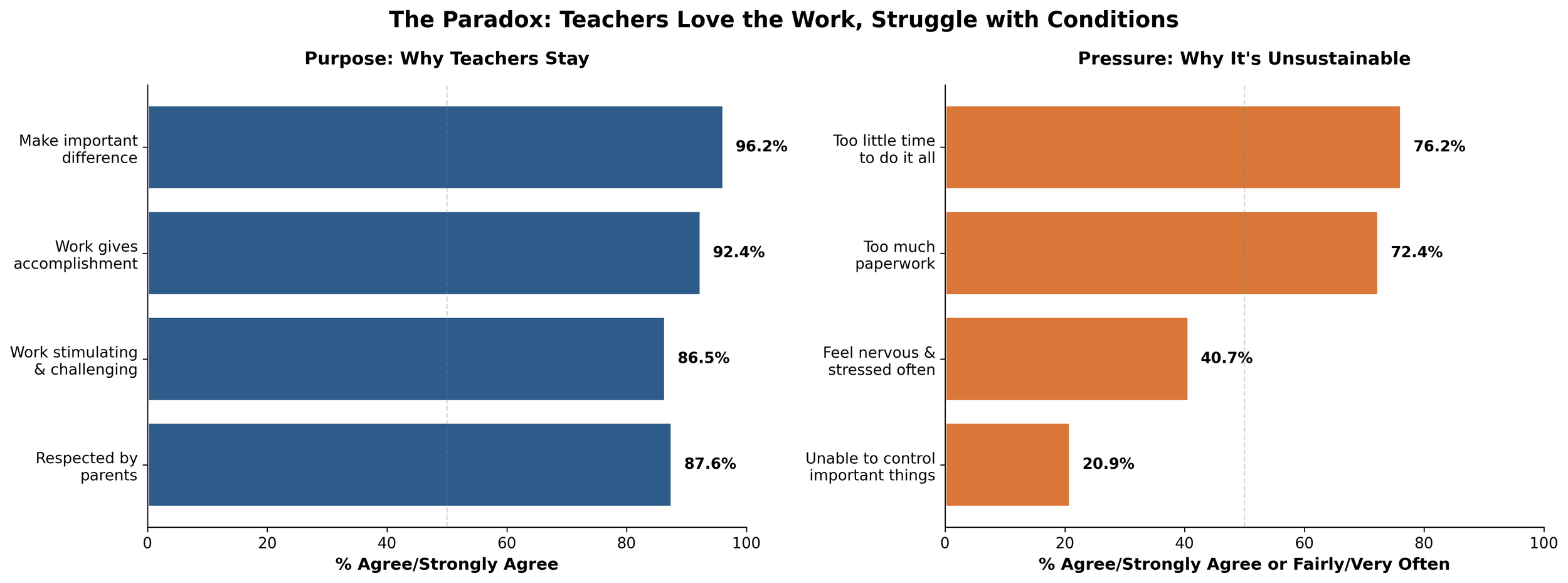

The Paradox of Purpose and Pressure

The clearest finding: teachers loved the work and struggled with the conditions.

96% agreed they make an important difference in students' lives

92% said their work gives them a sense of accomplishment

87% felt stimulated and challenged by their work

Yet simultaneously:

76% felt there was too little time to do all there is to do

72% reported too much paperwork and record-keeping

41% felt nervous and stressed fairly or very often

21% felt unable to control important things in their lives fairly or very often

This wasn't burnout from meaningless work—it was exhaustion despite meaningful work. Teachers were deeply committed to their purpose while drowning in conditions that made it nearly impossible to fulfill.

Side-by-side bar charts showing the paradox of teacher experience. Left side shows purpose (blue bars): 96% make important difference, 92% feel accomplishment, 87% find work stimulating, 88% feel respected by parents. Right side shows pressure (orange bars): 76% have too little time, 72% report too much paperwork, 41% feel stressed often, 21% unable to control important things.

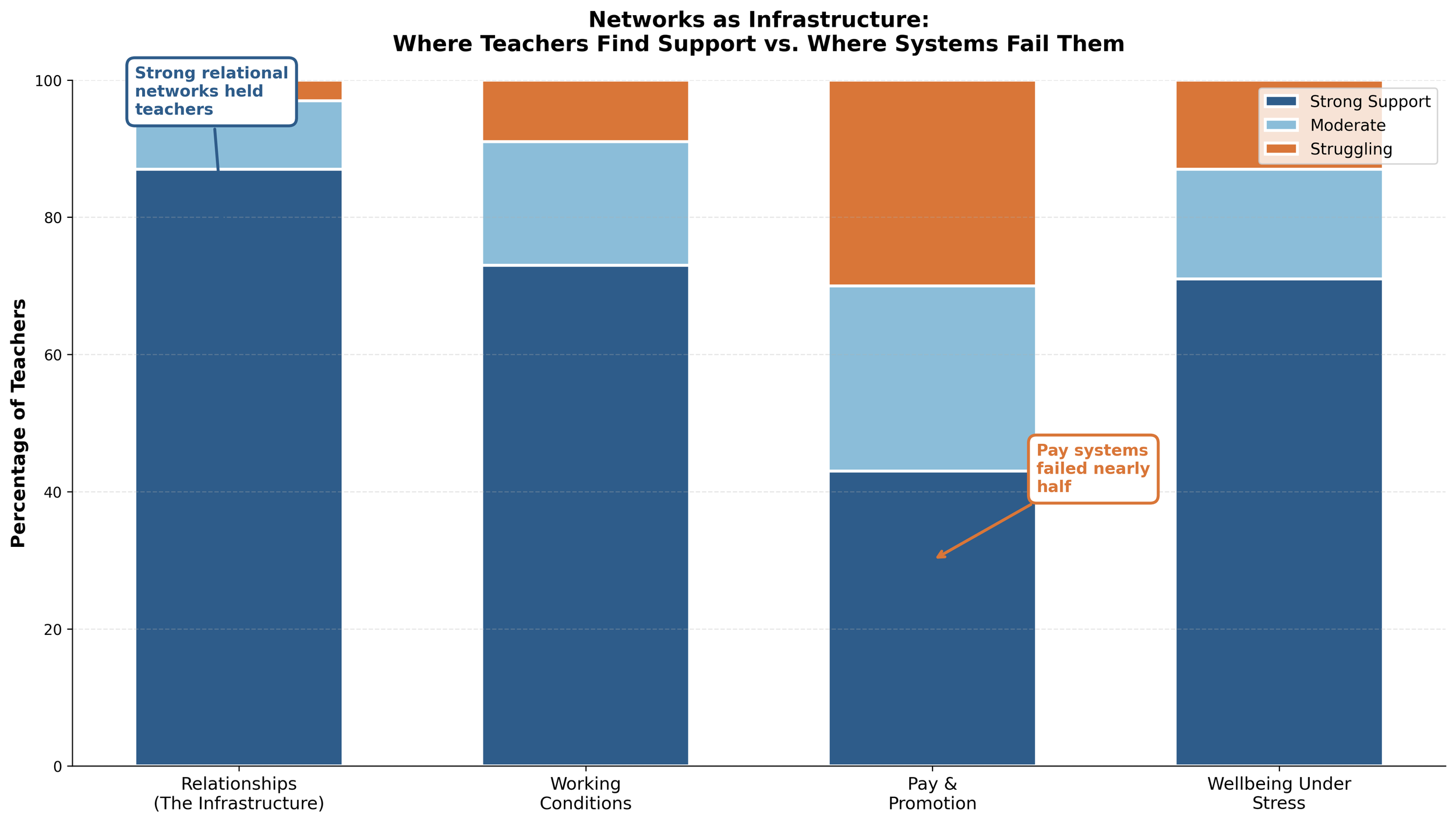

The Invisible Infrastructure That Held Them

What kept teachers going? Relationships.

87% felt colleagues cared about them

84% said colleagues shared ideas and resources

86% felt their supervisor respected their work

88% felt respected by parents

Horizontal bar chart showing what teachers value most in their work. Pay ranks highest at 15.5%, followed by colleagues/working with people I like at 14.4%, and achievement at 12.3%. Four of the top eight values are relationship-based, shown in blue bars. Pay is shown in orange to indicate it's a structural need competing with professional values.

These weren't just nice-to-haves. In a job where 55% felt underpaid (median salary: $30,001-$35,000) and 74% constantly thought about uncompleted tasks, relationships became infrastructure.

When teachers ranked what they valued most, "colleagues—working with people I like" came second only to pay. "Altruism—helping others" ranked fourth. These were teachers who valued connection, support, and mutual care—not isolation or autonomy.

What the Pandemic Made Visible

The data collection spanned the transition from "before" to "during" the pandemic. What's striking is what teachers reported even under these conditions:

71% felt confident handling their personal problems fairly or very often

57% felt they were effectively coping with important changes

Only 13% felt they couldn't cope with everything fairly or very often

These teachers weren't thriving under impossible conditions. But they were surviving—and the data hints at why: they had networks of support that held them.

Or at least, some of them did.

What the Data Taught Me About Invisible Infrastructure

Looking at this data now, with five years of distance and my own institutional upheaval, I see what I couldn't fully grasp in 2019: I was trying to document individual wellbeing when what I needed to understand was the ecology of support.

The variation in these numbers—21% who felt unable to control important things versus 71% who felt confident, 13% who couldn't cope versus 57% who were coping effectively—that variation isn't primarily about individual resilience.

It's about invisible networks.

Some teachers worked in schools where colleagues genuinely shared resources, where supervisors asked for their opinions, where feedback was helpful rather than evaluative. They could find what they needed, policies were clear, and they felt encouraged to try new things.

Others worked in the same types of programs—same funding streams, same accreditation standards, same licensing requirements—but experienced them completely differently.

The infrastructure was invisible. Unless you were inside it, you couldn't see what made the difference.

The teachers who scored high on depression or stress measures weren't failing as individuals. They were unsupported by invisible systems. The data were showing me that relationships weren't a "nice-to-have"—relationships were infrastructure, as foundational as adequate ratios, clear policies, or fair compensation. And when that infrastructure is invisible, we can't see where it's strong or failing until a crisis makes it visible.

Stacked bar chart comparing teacher support across four dimensions. Relationships show 87% strong support (blue), working conditions show 73% strong support, wellbeing under stress shows 71% strong support, but pay and promotion shows only 43% strong support with 30% struggling (orange), revealing where systems fail teachers despite strong relational networks.

The Evolution: From Individual to Ecological

My original research agenda was methodologically sound: validate the connection between wellbeing and inclusion, understand the mechanisms, develop interventions. It was framed entirely at the individual level—as if teacher wellbeing were primarily about personal resilience, stress management, or coping skills.

I didn't realize I was asking the wrong question.

The data kept pointing to something else: wellbeing isn't an individual attribute. It's an emergent property of networks.

This insight didn't come from the statistical analysis I'd planned. It came from sitting with the variation—noticing that teachers in similar circumstances reported wildly different experiences, and that the difference correlated not with their individual characteristics but with the quality of relationships around them.

You can't "support teacher wellbeing" with yoga classes, mindfulness apps, or resilience training. Those interventions treat wellbeing as something individuals cultivate within themselves. But the data showed that wellbeing emerges from being held by networks of connection—or fails to emerge when those networks are weak or invisible.

The pandemic revealed this. When schools closed and teachers coordinated remotely, invisible networks became starkly visible. Some organizations discovered robust webs of mutual support. Others discovered that what they thought were relationships were actually just proximity.

My research program got interrupted before I could complete the work I'd planned. But the interruption taught me something more important than any follow-up study could have: you can't study wellbeing without studying the systems that hold people.

What This Means for Organizations

If relationships are infrastructure, then making that infrastructure visible becomes essential work.

Organizations can't improve what they can't see. When relational networks remain invisible, we assume struggling teachers need individual interventions, miss where informal support systems already work, can't identify isolated groups before burnout, and fail to understand why the same policy succeeds in one building and fails in another.

The pandemic forced visibility. Organizations could suddenly see which teams had robust networks that translated to remote coordination, and which had been held together only by physical proximity.

But we shouldn't need a crisis to see our own systems.

What visibility requires:

Asking who people turn to (not just who they're supposed to turn to)

Mapping where information actually flows (not just formal reporting lines)

Understanding what informal leadership already operates (not just assigned roles)

Recognizing which connections are strong and which are fragile

This isn't about building new networks from scratch. Research on social networks consistently shows: the networks already exist. People are already turning to someone. Information is already flowing through certain channels. Informal leadership is already operating.

The question is whether we can see it.

And if we can see it, we can strengthen what's working instead of imposing something new, identify isolation before it becomes a crisis, understand why some interventions take hold and others don't, and support the informal leaders who are already holding things together.

The teachers in my study showed up for children with complex needs while feeling inadequately compensated, while drowning in paperwork, while the world collapsed around them. What sustained them wasn't individual resilience.

It was each other—when they could see and access each other.

What the Data Finally Revealed

Five years later, I finally understand what my data were showing me: relationships are infrastructure, and invisible infrastructure fails under stress.

The teachers who coped effectively weren't more resilient as individuals. They were held by networks that gave them access to resources, ideas, emotional support, and mutual recognition.

The teachers who struggled weren't failing. They were working in isolation that looked like proximity.

The variation I documented wasn't about individual differences in coping capacity. It was about whether the systems around teachers were visible enough to support them.

The research agenda I started in 2019 never got completed the way I planned. But the insight it generated—the one I couldn't see until I'd lived through my own experience of invisible systems—matters more than any follow-up study would have.

We can't support people we can't see. And we can't see people when we only look at individuals, not the networks that hold them.

This is what my data taught me. And it's what I have continued to learn—through partnerships with NYC Public Schools’ Division of Early Childhood Education and the Emotionally Responsive Practice Center at Bank Street College, through developing methods that make invisible systems visible, and through working with educators and leaders who are ready to see their own infrastructure.

The work continues. Just not in the form I originally planned.

Sarika S. Gupta, Ph.D. is the founder of Ecological Learning Partners LLC, which helps learning communities map and understand their networks of connection through contemplative mapping. Her research has been published in Young Exceptional Children, Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, and The New Educator.

About the Research

The “Survey of Teachers’ Wellbeing in Inclusive Early Childhood Classrooms” was conducted 2019-2021 with 272 lead teachers, primarily in Head Start settings. The study used validated instruments:

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Hunter College CUNY, and participants provided informed consent. This analysis presents aggregate findings to protect participant confidentiality.

Sample Demographics

71% identified as White; 13% Latinx; 11% Black or African-American; 5% other backgrounds

84% worked in Head Start programs; 8% in public/state-funded PreK; 8% in private programs/child care

97% female

Average 8.8 years experience as lead teachers

Mid-Atlantic region (primarily recruited through professional networks in this geography)

Study Limitations

The sample was predominantly White teachers working in Head Start settings in the mid-Atlantic region. The original research plan included expanding recruitment to capture more racially, ethnically, and programmatically diverse teacher experiences. This expansion was planned for 2021-2022 but did not occur due to program interruption.

Related Publications & Presentations

Gupta, S. S. (2019). Voices from the field: Why aren't we talking about teacher well-being with inclusion? Young Exceptional Children, 23(2), 59-62. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096250619846581

Gupta, S. S. (2020, February). Preliminary findings and ethical considerations in a study of ECSE teacher well-being. Research poster presented at Conference on Research Innovations in Early Intervention (CRIEI), San Diego, CA.

Gupta, S. S. (2020, April). Teacher well-being in inclusive early childhood settings: Preliminary findings and future directions [Roundtable Session]. AERA Annual Meeting San Francisco, CA. (Conference Canceled)

Gupta, S. S. (2021, February). Studying Early Childhood Teacher Wellbeing and Promoting Early Childhood Teacher Candidate Mindfulness. Invited panelist in the Spring 2021 Teaching and Learning Forum, "Ingenuity in Early Childhood: From Surviving to Thriving During Unprecedented Times," Montclair State University.

Note: This research was part of ongoing work at Hunter College CUNY that was interrupted due to career transitions. The insights gained have directly informed Ecological Learning Partners' approach to contemplative mapping.