Designing With, Not For: What Becomes Visible From Liminal Spaces

For 25 years, I've inhabited liminal spaces—those thresholds between belonging and exile where you're never quite inside, never completely outside. Professional spaces where I built meaningful relationships and contributed to significant work, but never quite understood the invisible rules that determined whose contributions got recognized and whose remained unseen.

Part of this was culture—being the daughter of professional émigrés from India, perpetually translating myself for others' comfort while trying to decode social conventions that weren't mine. Part of this was neurodivergence—a brain that processes patterns differently, that needs explicit structure where others seem to grasp implicit rules—within a family context of neurodivergence.

Liminal spaces are disorienting. But they offer something invaluable: a particular way of seeing. When you can't take belonging for granted, you notice whose work gets acknowledged and whose doesn't, which forms of collaboration get measured and which remain invisible, the gap between what institutions claim to value and what they actually recognize.

What I've learned from liminal spaces: institutions consistently miss significant collaborative strength because they only measure what's already familiar to them. And when institutions develop processes for people rather than with them, they miss something fundamental—they don't see the people actually doing the work.

The work is happening. The contributions are real. The relationships sustain institutional missions. But when patterns don't match what we've been trained to recognize as "connection" or "collaboration," the people doing that work remain unacknowledged.

When you design processes without the people who will navigate them, you design for the people you already understand—people whose ways of working match your own, whose contributions follow familiar patterns. Everyone else becomes invisible, not because they're not contributing, but because the measures weren't designed to see them.

What Liminal Spaces Reveal

When you inhabit liminal spaces long enough, patterns become clear that are invisible to people who've always belonged.

The faculty member who transforms students' lives through sustained mentoring but finds large social gatherings overwhelming. Their work advances the institution's teaching mission, but it doesn't show up at the receptions where "collegiality" gets assessed.

The researcher whose written analysis shapes policy decisions but needs processing time that rapid-fire meetings don't accommodate. Their thinking is rigorous, but it doesn't register in the quick exchanges that get coded as "engagement."

The administrator whose systematic work makes everyone else's projects possible but doesn't do the casual social navigation that builds visibility. Their contribution is foundational, but it remains invisible in assessments of who's "connected."

From liminal spaces, I can see: these are people whose contributions follow different pathways—pathways that traditional measures don't capture.

From Observation to Methodology

Living in liminal spaces taught me to observe with curiosity rather than judgment—to ask "what's actually happening here?" instead of assuming I should already know.

That shift transformed confusion into inquiry, what I'd experienced as limitation into insight.

If I couldn't intuitively read the unwritten rules, maybe I could map them systematically. If everyone else seemed to know something I didn't, maybe I could study how informal systems actually worked—and what those systems were missing.

When I began mapping with curiosity about what we're not measuring—tracking not just who speaks in meetings but who sends the emails that shift thinking, not just who networks at receptions but who builds the relationships that sustain collaborative work—different patterns emerged. The work was there all along. We just weren't designed to see it.

Designing With, Not For

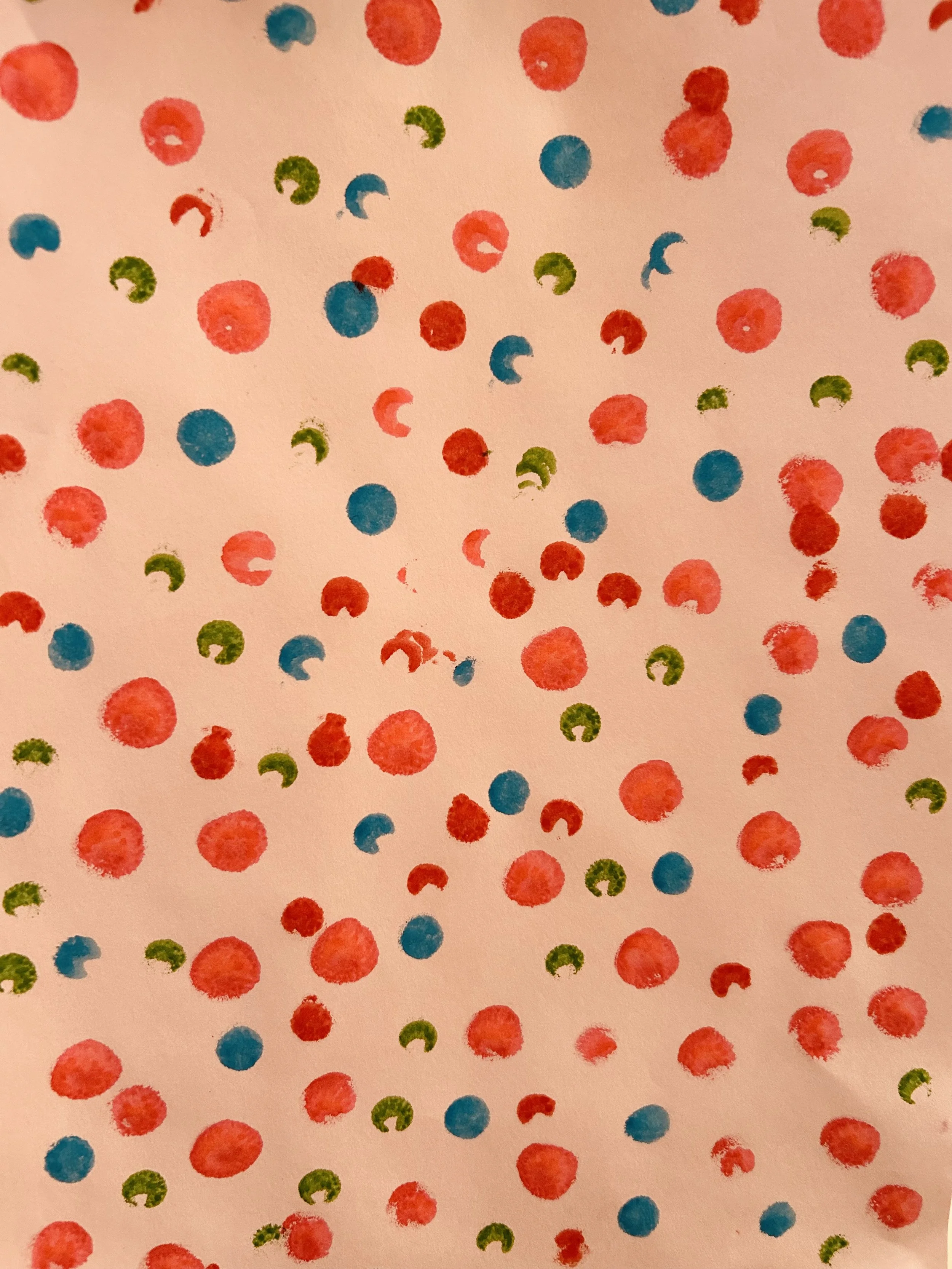

During my masters program in early childhood special education, I worked with young children who had trouble with social communication and interactions. Using an evidence-based model, I taught them to initiate and respond to social gestures, giving them a toolbox to make friends and play. The gains were powerful.

I understood that struggle—I had lived it.

The model was designed for children with these challenges, and it worked. But what I learned through practice was something the model itself didn't make explicit: the relationships we built, the practice we provided, the safe space to try and fail—that relational infrastructure was what made the structured intervention effective.

We weren't just implementing an evidence-based protocol. We were designing with children in real time—observing what they needed, adjusting how we practiced, building on what we were learning about neurodivergent ways of processing social information.

This distinction matters. The evidence-based model gave us tools. But designing with children—not just for them—is what allowed those tools to work.

Years later, I encountered research that named what I'd been learning: Participatory Design. Mona Leigh Guha and colleagues' work demonstrated how Participatory Design—a methodology that positions people as experts in their own experiences and genuine partners in design processes—creates more effective and inclusive outcomes by honoring how people actually know and contribute.

Dr. Guha introduced me to these Participatory Design principles, which aligned with what I'd learned about inclusion: genuine inclusion requires designing with people as partners, not for them as recipients.

Our collaborative self-study on facilitating a Participatory Design conversation series with early childhood teachers (Gupta & Guha, forthcoming) demonstrated what becomes possible: bringing together people who recognize varying circumstances and cultures, creating structures that meet them where they are rather than imposing predetermined processes.

Extending this approach further, this is what I mean by Participatory Design for relational capacity—not just co-designing better processes, but building the relational infrastructure that allows different people to participate as genuine partners in ways that work for how they actually process, connect, and contribute.

What This Means for Relational Capacity

In my last reflection, I wrote about building relational infrastructure during transition. Now I want to connect that to what liminal spaces reveal: relational infrastructure is most robust when it's designed with people who inhabit liminal spaces, not for them.

People in liminal spaces see what institutions miss. We experience the gap between what gets valued in theory and what gets recognized in practice. We know which collaborative work remains invisible, which contributions go unmeasured, which relationships sustain missions without acknowledgment.

What becomes possible when institutions invite people from liminal spaces to participate in designing the systems we all navigate?

Not just making informal rules explicit—though that helps. But applying Participatory Design principles: genuinely building with people whose contributions are currently invisible, positioning them as experts in their own experiences, asking how they actually work, what they need, what would allow their collaborative patterns to be recognized rather than missed.

When I taught preschool, my co-teacher and I learned that classroom community couldn't function if we only valued one way of participating. We needed all the children, which meant acknowledging all the children—their different ways of connecting, contributing, being in community together, whether verbally, nonverbally, with braille, sign language, picture communication symbols, or other modes of expression.

This is Participatory Design for relational capacity—building the infrastructure that allows different people to participate in ways that work for how they actually process, connect, and contribute.

It recognizes that practitioners are experts in their own experiences and need to be genuine partners in designing the systems they'll navigate. It allows for localization, cultural considerations, linguistic considerations—the context-specific needs that predetermined processes often ignore. It takes seriously what people in liminal spaces see—because liminal spaces reveal what belonging obscures.

What I'm Wondering About

When you assess who's "engaged" or "collaborative" in your institution—whether you're a tenure committee, a department chair, an administrator, or a colleague—are you seeing the whole person?

Circumstances beyond and within the professional context matter: a parent caring for sick children at home, someone managing a family health crisis, a colleague observing a holiday your institution doesn't recognize, someone navigating bullying or unresolved workplace conflict with no avenue to address it, a person managing their own health challenges while trying to meet expectations.

These real circumstances influence people's daily capacity and matter profoundly in getting work done—individually and collectively.

A teacher who doesn't ask questions in staff meetings but sends thoughtful follow-up emails. A colleague who remains quiet during planning conversations because they need time to consider newly presented information, then contributes crucial insights later. A professional who needs written materials rather than verbal-only formats to fully engage.

What if we asked different questions: Is time provided to consider rather than just react and discuss? Are multiple formats offered? Are people's actual life circumstances recognized as context for their contributions? Are you capturing the full range of ways people contribute? Or are you measuring who already has the capacity—the privilege—to navigate the particular forms of connection and immediate availability your institution has historically recognized?

When someone's contributions remain invisible, what might that reveal? Not about that person's capacity, but about what your measures miss?

What would you discover if you invited people from liminal spaces to participate in designing how you assess contribution, measure collaboration, build the relational infrastructure that allows diverse forms of excellence to flourish?

My years inhabiting liminal spaces taught me: the confusion I felt wasn't personal limitation. It was information about what institutions miss when they only recognize familiar patterns.

That insight reveals not just what's broken, but what becomes possible. When we design with people from liminal spaces rather than for them, we discover collaborative strength that was there all along. The work was happening. The relationships existed. The contributions were real.

We just weren't measuring in ways that allowed us to see them.

Liminal spaces aren't just places of struggle. They're sites of insight that reveal what institutions need to learn. The question is whether institutions are willing to learn from people who've never quite belonged—to invite us not just to adapt to existing systems, but to participate as genuine partners in designing systems that recognize multiple pathways to meaningful contribution.

We've known this in early childhood inclusion all along: access, meaningful participation, and infrastructural support aren't just for children—they're what practitioners need to do this work well.

That's what Participatory Design for relational capacity offers. That's what becomes visible when we take seriously what liminal spaces reveal.

Sarika S. Gupta, Ph.D.

Founder, Ecological Learning Partners LLC