What Makes Policy Sustainable? Practice Architectures for NYC's Early Childhood Expansion

Like many in early childhood education and intervention, I've been watching New York City's education transition with close attention. When Zohran Mamdani announced Kamar Samuels as Schools Chancellor and Emmy Liss as Executive Director of the new Office of Child Care, I felt something I haven't felt in policy announcements for a while: recognition of what our work actually requires.

Their commitments resonated with my experiences in the field: Samuels talks about seeing "students, not just as data points, but as whole people." Liss speaks of needing to "sustain our child care providers and educators." Mamdani promises community engagement that will be "tangible and actionable, not ceremonial or procedural." These are acknowledgments of what has been missing.

New York City is about to undertake significant scaling work—universal child care, class size reduction, integration initiatives, redesigned and more participatory parent engagement. In my years as a teacher with and without supports, as an instructional coach in Baltimore city, as a technical assistance provider with state departments of early intervention, as a professor in teacher preparation programs leading to state certification, I've learned that commitments like these require more than good intentions. These commitments require the conditions that help people sustain them.

Across these contexts, I've seen that infrastructure matters as much as policy. When educators and families have the conditions they need to do relationship-intensive work, sustainable change becomes possible. When those conditions aren't in place, even the most committed practitioners struggle.

The question is: What does it actually take to build systems that sustain educators and families while they do this work?

What Teachers, Families, and Administrators Actually Need

From 2021-2023 I studied NYC preschool programs to understand how teachers navigate decisions about special education referrals and inclusion (Gupta et al., 2024). We talked with administrators. We examined program processes. We observed classrooms. We life mapped with teachers to understand how their own educational experiences shape their practice today. We listened to families describe navigating the system. Each group told us what they needed.

On language and naming what's hard:

Teachers struggled with how to describe what they were seeing. One teacher tried to describe differences in abilities and development by saying "I don't know how else to describe it but for lack of a better word, she's slow... I don't mean to sound - I just don't know how to word it. She's a little bit behind but I don't know if it's just because she's not ready or if she actually needs help." Another teacher spoke about her desire to help children and families: "That's where the emotions come into play and frustration, because definitely I really do want to help you. Not that I can't, but at the moment no one's allowing me to do that."

Families described not knowing where to start. "I didn't even know I could ask for an evaluation. Nobody told me that was a thing. I thought I just had to wait and see if he caught up." Another parent, already managing her child's behavioral and developmental needs, discovered the extent of delays only after an evaluation: "I didn't know to the extent of how behind he was." She wanted information earlier—not just about what to look for, but how to access help. "I wish the parents were able to know that this is actually a system that is provided because I wasn't aware."

Administrators described the challenge. "Teachers come to me and say 'this child is difficult' or 'this child has behaviors' and I have to spend 20 minutes figuring out what they actually mean."

On time and coordination:

Teachers described the reality of collaboration. "We find each other in a hallway... There's no time." Another detailed coordination challenges: "I have this child who has OT, PT, speech, special instruction - four different people coming to work with him. When do I talk to any of them? I see the speech therapist for 30 seconds when she picks him up. That's it. We're all just guessing what each other is doing." Teachers wanted dedicated planning time to coordinate services, opportunities to meet with colleagues before parent meetings instead of arriving unprepared where "we're all just saying stuff," and time to sit with individual children without leaving nineteen others unattended.

Families described exhaustion navigating transitions. One parent navigating from early intervention to CPSE to kindergarten placement described having "a separate page of notes of who I'm supposed to contact" as systems changed without coordination. The transitions felt "choppy" and left her making school placement decisions "based on something I have no information on." She captured the toll: "I feel like I'm fighting all the time. Fighting to get him services. Fighting to make sure they're actually doing what they said they'd do. Fighting to get anyone to listen to me. I'm exhausted."

Administrators described the bind. "Teachers need time to plan together, to coordinate. But I can't give them that time without coverage, and I don't have coverage. So they're planning in the hallway, they're texting each other at night. It's not sustainable."

On power and voice in decisions:

Teachers described frustration with mandates. "They make all these decisions about what we're supposed to be doing, and they've never been in my classroom. They don't know my kids. But I'm supposed to just follow the manual." Another wanted to be asked: "If someone had asked us - the people who are actually doing this work every day - we could have told them what would actually help. But nobody asked."

Families noted ongoing change and uncertainty. One parent described navigating "a constantly changing system" while trying to advocate for their children. The exhaustion of "fighting to get anyone to listen to me" reflected a failure of power-sharing. When parents made school placement decisions "based on something I have no information on," they had responsibility without authority.

Administrators described their own lack of power. "Teachers feel like they have no say. And honestly, a lot of times they don't. The decisions are made above me too. I'm just the messenger."

Everyone wanted to do right by children. The conditions to make that sustainable weren't yet in place.

This isn't about commitment or competence. It's about infrastructure—the conditions that enable people to enact policy meaningfully.

What Practice Infrastructure Looks Like

Language: Creating Shared Meaning

Create program-specific spaces where teachers develop actual words to talk about what's hard—language grounded in children's abilities and development rather than jargon or distancing phrases. When teachers say things like "that child" and "slow," they're showing where shared language hasn't yet developed. Design structures where they can explore their questions and build vocabulary for differentiation and individualization.

Translate system knowledge into plain language for families about what supports exist and how to access them. New York City has made substantial effort in this area—publishing family guides and offering webinars and information sessions—but when a parent says "I didn't even know I could ask for an evaluation. Nobody told me that was a thing," families are showing us where translation broke down. Even people in the field can find it confusing. Strengthen these efforts so families can make informed decisions.

Build safe spaces for administrators to share what's happening in their programs and brainstorm together—the kind of support already happening in borough pods led by social workers. When administrators say "Teachers come to me and say 'this child is difficult' or 'this child has behaviors,'" they're naming the need for shared language and instructional support that develops through cross-program conversations.

Time: Structuring Hours Differently

Structure time that matches how practice actually develops—dedicated hours for teachers to sit with their work and connect with colleagues and specialists about children's development, learning, and instructional programming.

Create a single point of contact that gives families back time—relieving them of managing multiple contacts and shifting information as the system changes around them.

Build protected time and structural authority for administrators to create what teachers and families need. When administrators say "Teachers need time to plan together, to coordinate. But I can't give them that time without coverage, and I don't have coverage," they're naming what's required: coverage models that make collaborative planning possible and decision-making authority over how professional time gets structured within their buildings.

Power: Co-Designing Systems

Create structures where teachers co-design what inclusion looks like in their program, with their children, in their community—not structures where they implement mandates designed by the city. When teachers shape practice alongside specialists and families, they build sustainable approaches grounded in classroom realities.

Create partnership structures where families are heard before they're "fighting to get anyone to listen to me," and can make placement decisions based on transparent information rather than "something I have no information on."

Build administrator agency into the architecture—authority to engage teachers as co-designers and families as partners in shaping children's programs, rather than positioning them as messengers for decisions made "above me too."

The Basic Conditions

These are the basic conditions that make relationship-intensive work sustainable for teachers, families, and administrators at every level of the system.

There's a name for this infrastructure: practice architectures. Practice architectures are the arrangements—the conditions, structures, and relationships—that enable or constrain what people can actually do in their work (Kemmis et al., 2014). Language needs map onto what researchers call cultural-discursive arrangements—the ways we create shared meaning. Time needs map onto material-economic arrangements—the structures and resources that shape our hours. Power needs map onto social-political arrangements—who gets to shape the work (Kemmis & Grootenboer, 2008).

When we design practice architectures, we arrange the conditions that make meaningful practice possible. Potential costs of not building practice architectures with a new initiative are turnover, burnout, and failed implementation. Practice architecture design isn't additional cost—it's redirecting resources we're already spending to create the conditions practitioners need to implement research-backed policies.

Building Practice Architectures at the Program Level

In 2018, the Center for Young Children at the University of Maryland reached out to me for consultation on inclusion. The program had commitments in place: a full-time special educator, teachers with dual certification, partnerships with outside service providers. But teachers were saying "I don't feel comfortable or able" to implement inclusion. Some asked "Is that child really going to stay?" Others requested concrete strategies for specific disabilities—technical fixes that suggested they were looking for certainty in work that requires ongoing collaborative sense-making.

What was missing were the conditions that would enable teachers to enact inclusion.

Working in partnership with the administrative team, we designed a six-month "Conversations About Inclusion" series (Gupta & Guha, 2019) that built practice architectures across those three dimensions.

On language:

Teachers initially lacked shared ways of talking about inclusion. Through a structured SWOT analysis, identity brainstorming, and collaborative visioning, faculty developed new language together. By the end, they could articulate: "All children have the right to access, participate, and receive support to meet their full growth potential." This created what researchers call semantic space—the conceptual room educators needed to think together about their practice.

On time:

CYC teachers said they needed "more time to be more accountable for all kids." But time was finite. What changed was how time was structured: mixed-classroom planning teams, reflection notebooks, protocols for collaborative dialogue. We created 'Mixing Ideas' sessions—a participatory design technique originally developed for working with children (Guha et al., 2004)—where five teacher teams collaboratively blended their individual inclusion statements into one shared vision.

On power:

We used Participatory Design principles (Muller, 2008; Sanders, 2003) to position teachers not as recipients of inclusion policy but as co-designers of what inclusion would mean at their school. The administration created conditions for faculty to build shared vision together. The final CYC Statement on Inclusion represented all voices because all voices shaped it.

We didn't change policy. We built the culture of practice that made the policy sustainable.

Teachers moved from "I don't feel comfortable or able" to collaboratively developing action plans for the coming year. They identified priorities—supporting children's developmental and behavioral needs, strengthening partnerships with families and service providers, ensuring curriculum addresses everyone's needs. Not because someone told them these should be priorities, but because the practice architectures enabled them to see what their practice required.

Practice architectures look different at different system levels. At CYC, we built them within one program. But what do leaders do when they're responsible for building practice architectures across entire systems?

Building Practice Architectures at the State Level

Between 2009-2010, I interviewed state early intervention program coordinators navigating a federally-mandated shift in data collection practice. Years later, colleagues and I returned to those interviews to ask: What leadership practices actually helped practitioners navigate uncertainty when practice architectures weren't yet in place?

Using qualitative secondary analysis, we reframed the challenges coordinators reported through a strengths-based lens (Gupta et al., 2023). Five leadership practices emerged—all aligned with what implementation scientists call facilitative administration, the type of leadership that creates clear communication protocols and feedback loops to support practitioners adjusting to new practices.

Meeting practitioners where they are. State EI coordinators acknowledged practitioner resistance as a starting point for building buy-in, not an obstacle to overcome. Practitioners "did not understand at all the importance" of the new data collection practice. Rather than push harder, coordinators created feedback loops: listening to concerns, then framing change together until practitioners realized "it's probably the best that we're going to do. And no it's not perfect but it's what we've been given and we're going to make the best of it."

Identifying leaders. State EI coordinators designated clear roles when administrative authority was unclear. One assigned a single staff member responsibility for "training, dissemination of information, collecting the data, reviewing the data, analyzing the data." This clarity reduced practitioner confusion about who to ask when problems arose.

Creating consistent procedures. When measurement protocols were inconsistent, coordinators built reliable processes. Several created online databases for data entry. One tied data entry to the required service plan process so practitioners couldn't complete one without the other.

Readying professionals. State EI coordinators built capacity through protected time and partnerships. One described statewide trainings followed by online materials and ongoing messages to practitioners. When new staff arrived without training, they "conducted a training of about 300 folks... and videotaped that training" for ongoing access.

Building relationships. EI coordinators prioritized availability and individual follow-up to bridge infrastructural gaps. One maintained "an extremely close relationship with providers... every single provider feels welcome to call." Several emphasized partnerships with universities for ongoing technical assistance.

These weren't abstract leadership competencies. They were concrete actions state EI coordinators used when conditions seemed impossible: resistant practitioners, unclear administrative structures, inconsistent protocols, insufficient initial training, fragmented coordination.

The EI coordinators who successfully guided their states through transition explicitly attended to building the practice architectures—the language, time, power arrangements, and relationships—that would make new practices sustainable.

For NYC, this shows what systems leaders do when they can't hand practitioners a complete practice architecture—they build it iteratively, alongside implementation, by meeting people where they are and creating the structures practitioners need as challenges emerge.

Considerations for NYC's Expansion

New York City is about to undertake work that will ask educators to hold more complexity, build more relationships, coordinate more systems, and sustain more nuanced practice than ever before.

Universal child care means enrolling children whose families have never navigated formal education systems. Class size reduction means hiring educators who will benefit from support implementing evidence-based practice. Integration initiatives mean bringing together school communities with different histories, resources, and ways of working. Redesigned parent engagement means building authentic partnership with families who have experienced schools as sites of exclusion.

This work becomes sustainable when educators have shared language to talk about what quality means across difference, structured time to plan collaboratively rather than finding each other in hallways, and power to shape what their practice looks like rather than implementing mandates designed elsewhere. It becomes sustainable when families have clear information about what help exists and how to access it, when transitions between systems don't require separate contacts and starting over, and when parents have partners in navigation rather than advocating alone.

These are practice architectures. And early implementation windows offer the opportunity to design them intentionally. What would it mean to approach NYC's expansion with practice architecture design as central rather than peripheral? What shifts if we ask not just "What policies do we need?" but "What arrangements will enable people to enact these policies meaningfully?"

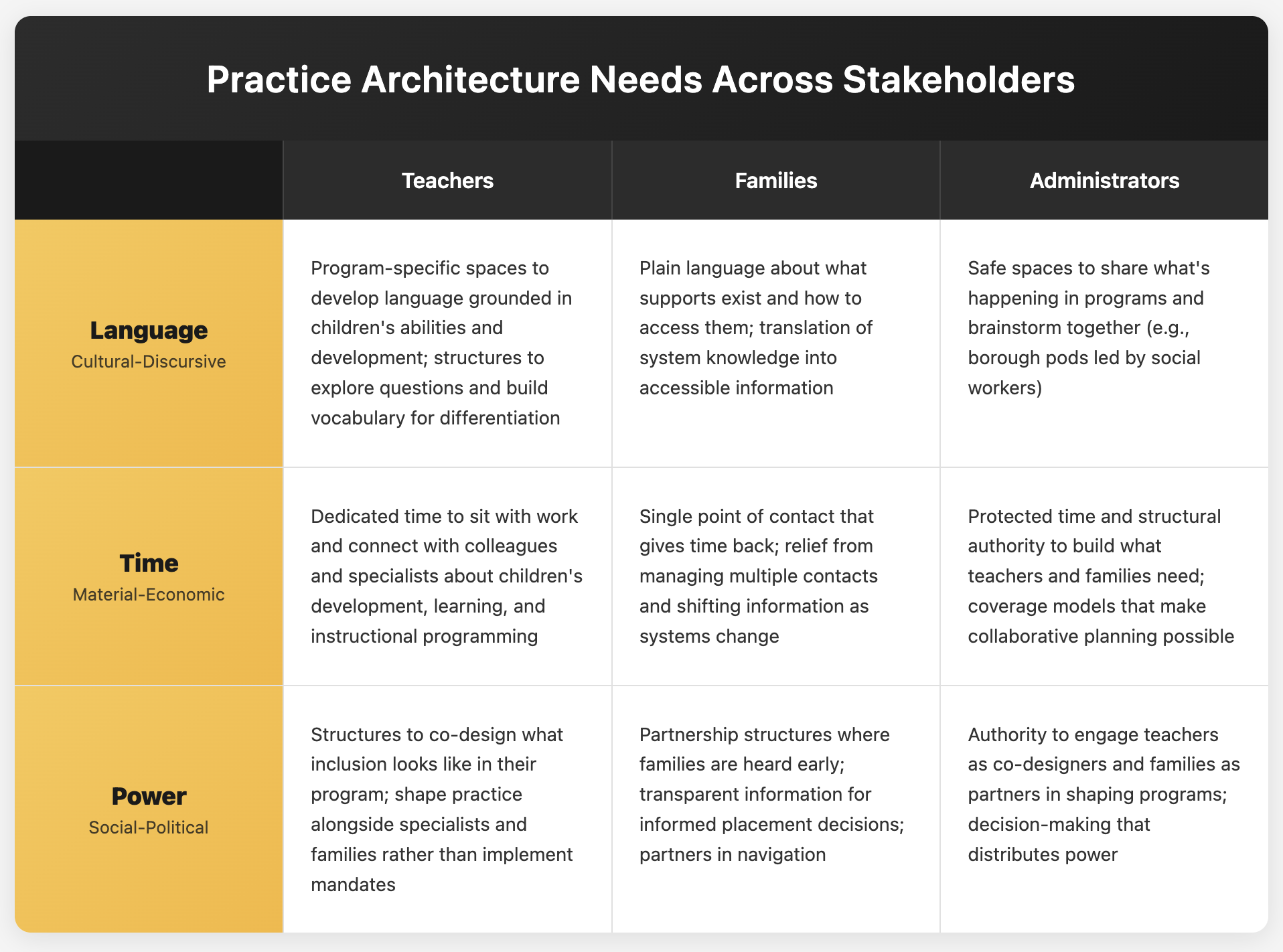

Table 1: Practice Architecture Needs Across Stakeholders

Table showing practice architecture needs across three stakeholder groups (Teachers, Families, Administrators) and three dimensions (Language, Time, Power). Each cell describes specific structural conditions needed: teachers need spaces to develop shared language and time for collaborative planning; families need plain language information and single points of contact; administrators need authority to build locally responsive structures and protected time to support both groups.

Sustainable change becomes possible when we build practice architectures intentionally. When we build them reactively, after patterns are set, the work is harder—but still doable.

The table above offers a starting framework. Not every initiative will require all nine elements simultaneously, but early implementation windows are the time to ask: Which practice architectures does this initiative require? How will we build language, structure time, and distribute power so practitioners can actually enact what we're asking of them? These questions matter as much as the policies themselves.

NYC's new administration has named what matters. Building the conditions that make it sustainable—connecting what research shows, what policy requires, and what implementation actually needs—is the work of early implementation windows. That's the work ahead.

References

Guha, M. L., Druin, A., Chipman, G., Fails, J. A., Simms, S., & Farber, A. (2004). Mixing ideas: A new technique for working with young children as design partners. Proceedings of Interaction Design and Children: Building a Community, 35-42. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/1017833.1017838

Gupta, S. S., & Guha, M. L. (2019). "Conversations About Inclusion" at the Center for Young Children at the University of Maryland, College Park: Final Summary. https://ecologicallearningpartners.com/inclusion-cyc-report

Gupta, S. S., Cheatham, G. A., Strassfeld, N., Zhu, X., Medellin, C., & Nagasawa, M. (2024). Examining the ecology of preschool inclusion in New York City: A mixed-methods study underway. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, OnlineFirst. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/14639491241229229

Gupta, S. S., Sherif, V., & Zhu, X. (2023). Re-examining state Part C early intervention program coordinators' practices through a positive lens on leadership: A qualitative secondary analysis. The Qualitative Report, 28(2), 517-543. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2023.4786

Kemmis, S., & Grootenboer, P. (2008). Situating praxis in practice: Practice architectures and the cultural, social and material conditions for practice. In S. Kemmis & T. J. Smith (Eds.), Enabling praxis: Challenges for education (pp. 37-62). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4020-6688-0_3

Kemmis, S., Wilkinson, J., Edwards-Groves, C., Hardy, I., Grootenboer, P., & Bristol, L. (2014). Changing practices, changing education. Singapore: Springer. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-981-4560-47-4

Muller, M. J. (2008). Participatory design: The third space in HCI. In A. Sears & J. Jacko (Eds.), The human-computer interaction handbook (2nd ed.) (pp. 165-186). New York, NY: L. Erlbaum Associates. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.5555/1226736.1226756

Sanders, E. B. N. (2003). From user-centered to participatory design approaches. In J. Frascara (Ed.), Design and the social sciences (pp. 18-25). London, UK: CRC Press. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.1201/9780203301302-4/user-centered-participatory-design-approaches-elizabeth-sanders

Sarika S. Gupta, Ph.D., is the founder of Ecological Learning Partners LLC. She builds practice architectures that connect implementation, research, and policy through contemplative mapping of self and system—work that makes invisible relational infrastructure visible. This piece extends thinking developed in "Building Relational Infrastructure: Questions for a Moment of Transition."