Finding Ground: From Reactive Accommodation to Conscious Positioning

Several weeks into a new faculty position, I found myself in a department meeting where my chairperson asked me to share my experience from my previous university, where the special education program had operated separately. I'd mentioned this to her privately, as context. Now she was asking me to share it publicly, in a discussion about integrating our own departments—a proposal that, I would later understand, carried significant political weight.

I didn't know the history. I didn't know who wanted what or why. But everyone was looking at me, waiting for the new person with relevant experience to speak.

"Yes," I said. "Special education was a separate entity from the other departments in the school."

I watched faces shift—some disappointed, some satisfied. I'd meant it as a simple observation. But I could see it had landed as something else.

What I notice now, looking back, is what I told myself: "I should have been smoother. I should have read the room better. I should have known."

The weeks that followed established a pattern I'm still working to understand. I replayed the meeting constantly. I avoided certain colleagues. When the integration discussions continued, I stayed quiet. I told myself I was being cautious, but what I was actually doing was shrinking back—deciding that not speaking was safer than risking saying the wrong thing again.

I've been asking myself since: Was that caution? Or was it something else?

—

I considered my positioning and shifted the question to an actionable inquiry: What was I actually doing in moments like that meeting?

Organizational psychologist Tasha Eurich writes about two types of self-awareness: external (understanding how others perceive you) and internal (knowing your own values, thoughts, reactions) (Eurich, 2017). Reading her work, I recognized something: I'd developed substantial external self-awareness. I could track emotional temperatures in rooms, sense what people wanted to hear, notice subtle shifts in dynamics. But internal self-awareness? The capacity to know what I thought, independent of what I sensed others wanted me to think? That was murkier.

The neuroscience here is worth considering. When we try to hold multiple perspectives simultaneously while suppressing our own, we're asking a lot of our executive function—the brain's capacity for planning, focus, and decision-making (Diamond, 2013). Working memory, which supports executive function, has finite capacity (Baumeister et al., 2007). So when I used that capacity to track everyone else's positions while avoiding my own, I was essentially running analysis on incomplete data. The exhaustion I have long felt after meetings wasn't just social anxiety. It was cognitive load.

This made me curious about my contemplative practice. By 2018, I'd been studying Iyengar yoga for ten years, with two years of formal pranayama training. The practice had taught me to observe thoughts without being swept away by them—what Patanjali's Yoga Sutras call chitta vritti nirodhah, the stilling of the fluctuations of mind (Yoga Sutra 1.2). But I wondered if I'd confused this witnessing awareness with something else.

Research on contemplative practice distinguishes between equanimity and what might be called "strategic neutrality" (Desbordes et al., 2015). Equanimity involves clearly seeing what's present while maintaining inner balance. It doesn't mean suppressing what you see or denying your response to it. Strategic neutrality, on the other hand, might involve actively avoiding a position to maintain external equilibrium.

The distinction matters. One practice builds capacity, while the latter depletes it (at least for me).

I was also curious about interoception—our capacity to sense internal states (Critchley & Garfinkel, 2017). Studies show that contemplative practice can develop interoceptive awareness, and that this awareness connects to knowing your own emotions and, potentially, your own perspectives (Farb et al., 2015). My Iyengar yoga practice had certainly developed my physical interoception. I could feel exactly where my body needed support. But had I applied that same attention to sensing my own intellectual or relational positions? Or was I only using interoception to sense others' comfort levels?

What made this particularly interesting was the parallel to my professional work. Looking back, I recognize 2018 as when my contemplative mapping methodology was beginning to emerge, though I couldn't name it then. I'd been developing questions for educational settings—"What patterns and spaces create psychological safety?" or "Whose perspectives get centered?"—but I hadn't turned those questions toward my own patterns. What infrastructure was I creating when I prioritized reading others over knowing myself? Whose comfort was I centering? I could feel something about relational dynamics but didn't yet have frameworks or language to articulate what I was sensing.

This is the heart of what I now call contemplative mapping: using systematic observation to make visible the relational infrastructure we're embedded in. Whether I'm working with learning communities navigating institutional dynamics or mapping my own patterns, the methodology is the same—create enough structure to see what's actually happening, not what we assume is happening.

Research on teacher emotional labor provides a framework for understanding this depletion. When teachers chronically suppress authentic responses while tracking students' reactions, they experience higher burnout (Yin et al., 2019). I was doing something similar—constantly monitoring relational data, sitting with embodied sensations of others' comfort and discomfort, but never mapping my own position in that field. I was collecting data about everyone else's experience while my own remained unmapped.

I kept returning to this question: Could I see complexity and know where I stood? Could I track multiple perspectives and articulate my own?

—

I've been sitting with the concept of continuous calibration, a Buddhist teaching that appears throughout practice—mindfulness (sati) as ongoing attention to changing conditions, adjusting action (Right Action, samma kammanta) based on what's actually arising rather than fixed ideas (Bodhi, 2011). This calibration assumes impermanence (anicca)—everything changes, including our understanding—and no fixed self (anatta) to defend.

I started wondering: What's the difference between skillful calibration and what I was doing?

Skillful calibration, as I understand it from Buddhist teaching, involves seeing clearly what's present and responding appropriately—but from a grounded position. You know your values (Right View, samma ditthi), and from that ground, you adjust how you express them based on conditions. You might speak more directly with one person, more gently with another. You might act now or wait. But the adjustments come from clarity about your intentions and understanding, not from trying to disappear (Thich Nhat Hanh, 1998).

What I was doing felt different. I wasn't adjusting my expression based on wisdom about conditions. I was trying to figure out how to avoid having a position at all—reading the room to determine what response would let me survive without anyone being upset, a pattern I learned in early childhood.

The confusion, I think, came from misunderstanding anatta (no-self). I'd interpreted "no fixed self" as "no position at all"—as if being fluid meant being formless. But that's not quite what the teaching suggests. Anatta points to the absence of a permanent, unchanging essence—not the absence of discernment, values, or the capacity to know your own mind in any given moment (Analayo, 2003).

This distinction matters: Buddhist calibration seems to involve responsiveness from ground, not groundlessness masquerading as flexibility.

I'd been carrying this pattern most of my life, but that 2018 faculty meeting crystallized the exhaustion of constant calibration as something I needed to investigate. Still, I didn't have language for what I was experiencing—not until a moment with my daughter made it impossible to ignore.

—

I saw the pattern clearly at an indoor play space.

My four-year-old daughter had been waiting at the bottom of a slide. Two girls approached her and I heard them say, "We need to go first."

My daughter said something to them and stepped aside.

This wasn't the first time, and maybe she was just being her kind and generous self—but I verbally reminded her from a distance to stay in line. The two girls looked at me with an expression of guilt.

What happened in my body and brain in that moment? My limbic system activated—I felt anger rise at the situation unfolding. Not at my daughter or the girls (they were all preschool-aged children learning social negotiation), but at the pattern I was witnessing install itself. My early childhood teacher training wanted me to step in and facilitate toward equity and fairness. But my prefrontal cortex, my executive function, caught up: these were children learning to interact, take turns, and negotiate. They needed to work it out themselves.

I inhaled, then exhaled. That breath created space between my initial reaction and my response. I prompted my daughter to stay in line without stepping into the children's interaction.

What stayed with me wasn't just what happened between the children. It was recognizing what my daughter was learning through observation: that accommodation was default, that backing down was good, that what you wanted mattered less than avoiding friction.

What have I been teaching her about how to move through the world?

Later during a run, I used the movement to process what had happened—to turn the experience around, examine it from different angles, and apply language to what I'd felt. Running, like writing, helps me externalize what's internal. The anger wasn't just about one playground moment. It was about watching my lifelong pattern of reactive accommodation begin to replicate itself in my daughter. What I'd been experiencing since 2018 finally had a frame: I needed self-to-system regulation, not just system awareness.

—

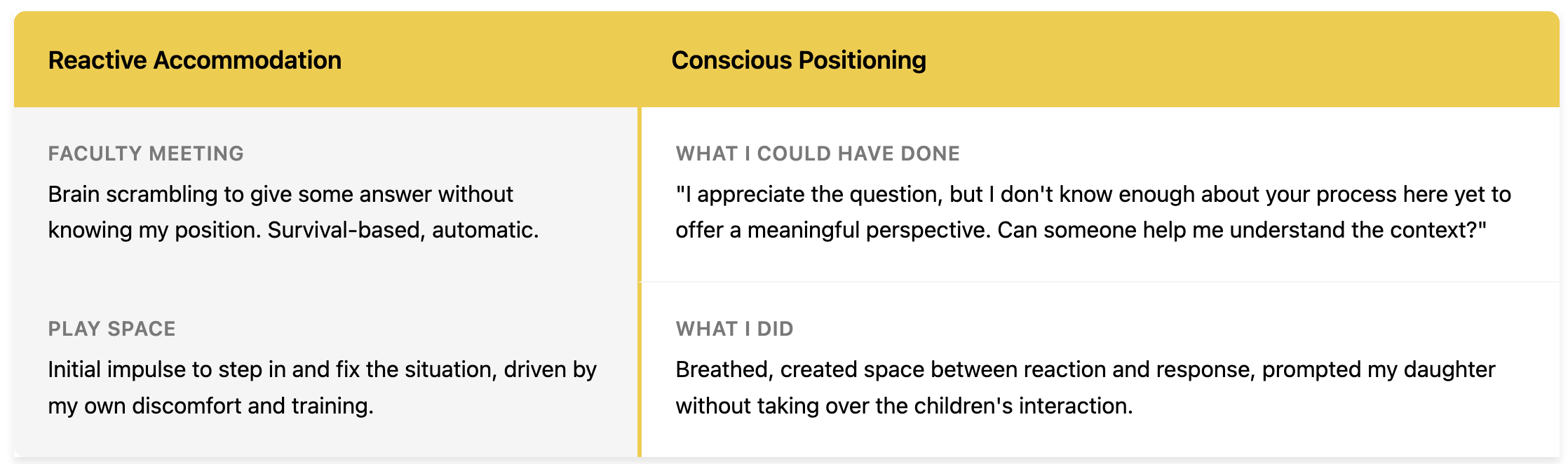

I started noticing the difference between two patterns that look similar on the surface but feel entirely different to inhabit:

A visual comparison of reactive accommodation versus conscious positioning, showing examples from a faculty meeting and playground interaction.

Conscious positioning means knowing what I think—even if what I think is "I need more time to know"—and choosing how to engage from that awareness. Sometimes I still accommodate. Sometimes I assert. Sometimes I stay quiet. But there's ground under the choice now.

—

Some practices that have helped me build this capacity:

Breath. Both Iyengar yoga and Buddhist practice teach that conscious breathing—simply inhaling and exhaling—is the foundation of self-regulation (Iyengar, 1966; Bodhi, 2011). Neuroscience confirms this: controlled breathing activates the parasympathetic nervous system, moving us from reactive to responsive states (Gerritsen & Band, 2018). When I initially felt anger at the playground, slowing down to breathe created space between reaction and choice.

Engage in embodied practice. Running is one of my a contemplative practices—a way to process experiences I can't think through while sitting still. The repetitive movement helps me turn situations around, examine them from multiple angles, and find language for embodied responses.

Process privately. I write out my thoughts—all the complexity, the analysis—before trying to articulate a position. My neurodivergent brain seems to need this. Once I've written everything, I can often find the core: "Here's what I think" or "Here's what I need to know more about."

Notice the preamble. I catch myself starting sentences with "I'm not saying X is wrong, and I see why people might think Y, but..." Now I'm practicing: "I think Z." If people want more context, they ask.

Build in time. When someone puts me on the spot now, I'm learning to say "Let me think about that" or "I'd need more context to offer something useful." Or I just wait to answer if it's an email or text. What should have been my response in that first faculty meeting has become something I can actually do.

Practice with my daughter. The playground has become a place to practice. "You were here first. You can go now." Simple statements. No elaborate justification. She needs to see that having a position isn't dangerous. I need to practice having one.

Buddhist psychology talks about right speech—communication that's truthful, timely, kind, and beneficial—rather than a correct perspective (Bodhi, 2011). I'd been focusing heavily on "kind" and "beneficial" while underweighting "truthful"—not lying, but being truthful to myself about what I actually thought. Reactive accommodation was a form of self-abandonment that I'd mistaken for compassion.

—

Shortly after that faculty meeting, I read Pema Chödrön's Comfortable with Uncertainty and began training, as she describes it, as a "warrior of non-aggression"—using embodied practices like yoga and, later, running, not to become certain but to stay present with not-knowing.

What's lessening is a particular exhaustion—the kind that came from constant self-monitoring, from trying to figure out what everyone needed me to be. Not because everyone suddenly understands me, but because I'm not asking them to anymore.

I'm also noticing who's actually interested in connection versus who appreciated my neutrality because it made me easy to be around. Some relationships have shifted. That's been uncomfortable, but necessary. Some relationships are surprising and thriving.

For my daughter, I positively reinforce her saying "I want a turn" now without checking my face first. She doesn't automatically yield anymore. She's learning that "I was here first" is a complete sentence. We're both still learning, but she seems to be building different default patterns than I did. I'm grateful for opportunities like this to help me examine and course correct—this is inquiry at its heart.

For my work, something's clarifying. My writing feels sharper. I'm stating positions rather than observing from the margins. For years, I've been skilled at reading others' positions, mapping their infrastructure, seeing what's invisible in their systems. But I'd missed what was invisible in my own patterns—the infrastructure I was creating through constant accommodation. Now I'm applying the same contemplative mapping methodology to myself that I use with learning communities.

—

My daughter goes down the slide when she's ready now. Sometimes she lets other kids go first—and I'm learning to trust that she's building her own ground while staying open to others.

Meanwhile, what I’m learning is that self-to-system regulation requires sensing both the relational field AND my own position within it—which means continually asking: When am I calibrating from ground versus groundlessness? When does accommodation serve connection, and when does it erase me? What am I teaching through how I move through the world?

I haven't resolved these questions, but I am okay sitting with the uncertainty they invite.

References

Analayo, B. (2003). Satipatthana: The direct path to realization. Birmingham: Windhorse Publications. https://www.buddhismuskunde.uni-hamburg.de/pdf/5-personen/analayo/direct-path.pdf

Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., & Tice, D. M. (2007). The strength model of self-control. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(6), 351-355. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00534.x

Bodhi, B. (2011). What does mindfulness really mean? A canonical perspective. Contemporary Buddhism, 12(1), 19-39. https://doi.org/10.1080/14639947.2011.564813

Chödrön, P. (2002). Comfortable with uncertainty: 108 teachings on cultivating fearlessness and compassion. Boston: Shambhala Publications.

Critchley, H. D., & Garfinkel, S. N. (2017). Interoception and emotion. Current Opinion in Psychology, 17, 7-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.04.020

Desbordes, G., Gard, T., Hoge, E. A., Hölzel, B. K., Kerr, C., Lazar, S. W., ... & Vago, D. R. (2015). Moving beyond mindfulness: defining equanimity as an outcome measure in meditation and contemplative research. Mindfulness, 6(2), 356-372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0269-8

Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 135-168. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750

Eurich, T. (2017). Insight: Why we're not as self-aware as we think. New York: Crown Business.

Farb, N., Daubenmier, J., Price, C. J., Gard, T., Kerr, C., Dunn, B. D., ... & Mehling, W. E. (2015). Interoception, contemplative practice, and health. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 763. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00763

Gerritsen, R. J., & Band, G. P. (2018). Breath of life: The respiratory vagal stimulation model of contemplative activity. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 12, 397. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2018.00397

Iyengar, B. K. S. (1966). Light on yoga. New York: Schocken Books.

Patanjali. (n.d.). Yoga Sutras (B. K. S. Iyengar, Trans.). (Sutra 1.2).

Thich Nhat Hanh. (1998). The heart of the Buddha's teaching. New York: Broadway Books.

Yin, H., Huang, S., & Chen, G. (2019). The relationships between teachers' emotional labor and their burnout and satisfaction: A meta-analytic review. Educational Research Review, 28, 100283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2019.100283

Sarika S. Gupta, PhD, is founder of Ecological Learning Partners LLC. Traditional professional preparation and development in education focuses on practice and competencies while skipping over the person. My work helps practitioners reconnect with themselves, their why, and other people through contemplative mapping of self and system.