Building Educator Capacity for Responsive Care: Infrastructure Recommendations for NYC’s 2-Care Implementation

In January, I wrote about practice architectures and what makes policy sustainable. With 2-Care launching in fall 2026, this piece translates that framework into recommendations for building educator capacity—exploring what infrastructure for responsive caregiving might look like when designed with the people closest to the work.

New York City’s expansion of universal early care and education to two-year-olds represents a historic opportunity—not just to add classroom seats, but to build the infrastructure that enables educators to provide the responsive, relationship-based care that two-year-olds and their families need.

As Mayor Zohran Mamdani recently stated: “Child care is not just a question of finding the funding. It is also a question of building infrastructure and the apparatus around it, and that requires you to stage this, as opposed to being able to do it all in one swoop” (Zaveri, 2026).

The difference between programs that enable children to thrive and those that struggle lies in the practice architectures—the conditions that shape what educators can actually do in their daily work. Implementation science shows that new programs frequently struggle to achieve intended quality, and meaningful implementation requires years of sustained effort even under favorable conditions (Fixsen et al., 2005).

This brief offers recommendations for building practice architectures that develop educator capacity for responsive caregiving. The term “educators” refers to all early childhood professionals working with two-year-olds: teachers in center-based programs, family child care providers, and home-based care providers. Individually and collectively their growth matters. The recommendations shared below draw on research in early childhood systems, contemplative approaches to professional development, and implementation science, and focus on what supports educators need to be skilled attuned practitioners with young children.

Early intervention and early childhood special education recognize reflective supervision, learning communities, and family partnerships as essential infrastructure for supporting young children’s development—even when implementation is inconsistent. These aren’t add-ons; they’re how educators build capacity for the relational, observational work that responsive caregiving requires. As child care expands to serve two-year-olds, some of whom may have Individualized Family Service Plans (IFSPs) or be the process of being referred or evaluated for an IFSP , child care educators need similar supports. These recommendations draw on research about what enables educators across early childhood settings to do this complex work well.

Understanding Practice Architectures

Practice architectures are the conditions that shape what educators can actually do. In a prior post on NYC’s early childhood expansion, I described these as questions about language, time, and power (Kemmis et al., 2014).

Language (cultural-discursive arrangements) shapes what can be said and thought. Do educators have language for describing what they observe? Can they articulate the developmental processes they’re supporting? Is there space to discuss the emotional demands of the work?

Time (material-economic arrangements) determines what can be done. Does the environment support toddler exploration? Are there enough hands to respond to individual needs? Is there time for observation, reflection, and family conversation? Can educators support themselves financially?

Power (social-political arrangements) governs what may be done. Who has authority to shape how care routines unfold? What gets assessed as “quality”? How are educators’ insights incorporated into program decisions?

These three dimensions work together. Professional development (language) depends on staffing ratios that allow time to apply learning (time) and accountability systems that support experimentation (power).

Why This Matters for Two-Year-Olds

Two-year-olds are not just “younger preschoolers.” They require fundamentally different caregiving.

The work is primarily relational and embodied. Two-year-olds learn through care routines. Feeding, diapering, nap time, separations and reunions—these moments are the curriculum. Educators read subtle cues, respond with appropriate touch and tone, stay present with children’s big emotions.

Individual children vary enormously. Some have extensive language, others communicate through gesture and sound. Some separate smoothly from parents, others need weeks of gradual transition. Responsive care depends on continuous observation and adaptation.

Families entrust their very young children to educators’ care. Building that trust happens through consistent communication, honoring family knowledge, and partnering in supporting children’s growing independence.

The emotional landscape is complex. Two-year-olds are developing autonomy, testing boundaries, and learning to express big feelings with limited language. Biting, hitting, meltdowns, and resistance are typical expressions of development, not defiance. Supporting children through these moments requires educators who can stay regulated, see behavior as communication, and respond with compassion. This depends on deep self-awareness—including recognition of implicit and explicit biases that shape how educators interpret and respond to different children’s behavior—and ongoing support.

What Research Tells Us About Building Educator Capacity

Research shows what builds these capacities.

Contemplative and reflective approaches build the capacity responsive caregiving requires. Contemplative practices support teacher development not just by reducing stress, but by building the self-awareness, reflexive capacity, and ability to stay present that enables responsive practice (McCaw, 2023). Structured opportunities to examine their own responses, notice patterns, and develop inner steadiness allow educators to remain attuned to children even in challenging moments.

Reflective supervision supports relationship-based practice in infant and early childhood settings. Rooted in infant mental health and social work traditions, reflective supervision creates a trusting relationship where educators can examine their emotional responses to their work (Paradis et al., 2021). When educators experience their supervision relationship as safe and supportive, this corresponds with reduced burnout and increased capacity for relationship-based practice (Shea et al., 2020; Tobin et al., 2024). For two-year-old settings where educators must interpret behavior as communication and stay emotionally present through challenging moments, reflective supervision provides essential support for developing and sustaining these capacities.

Educators learn through ongoing, collaborative inquiry—not one-shot training. One-shot workshops don’t transfer to practice without ongoing support—evidence documented since the 1980s (Joyce & Showers, 1982). Teachers don’t simply adopt practices from professional development; they actively adapt new approaches through continuous sense-making in their specific contexts (Marshall & Horn, 2025). This means educators benefit from sustained opportunities to try things, observe what happens, discuss with colleagues, and refine their approach.

Communities of practice sustain growth over time. Educators learning together through shared practice develop collective capacity that supports ongoing professional growth (Wenger et al., 2002). Initial training, even when effective, benefits from ongoing collegial support to maintain practice changes (Joyce & Showers, 1982). Continuing opportunities for collective learning—not just during implementation but as permanent infrastructure—support professional growth.

Adult well-being directly affects what adults can provide for children. Supporting adults’ capacity to manage stress and remain present shapes the quality of care and learning environments they create. Program approaches focused solely on curriculum show limited effectiveness without attending to adult wellbeing (Shonkoff & Fisher, 2013). A lack of adequate support can lead to burnout, stress, and depressive symptoms that may influence educators’ responsiveness to children (Jeon et al., 2024).

Preschool settings show what happens without adequate support of educator wellbeing. Young children face exclusionary discipline at higher rates compared to older students. Black children and children with disabilities experience particular harm (Gilliam, 2005; Zeng et al., 2019). These practices stem from adult factors—inadequate support, high stress, lack of resources—not from children’s behavior (Zinsser et al., 2019). Two-year-olds express themselves through behavior that requires skilled interpretation. Without practice architectures that support educator capacity, children are at increased risk of suspension and expulsion.

Core Recommendations for an Integrated Practice Architecture System

The following six recommendations work together as an integrated system for building educator capacity. They address all three practice architecture dimensions and create conditions where educators can develop into skilled, responsive practitioners.

1. Sustained Learning Communities

What this is: Small groups of educators (8-12) meeting monthly throughout the implementation year and beyond, engaging in collaborative inquiry about their actual practice with two-year-olds.

What this looks like in practice:

Educators bring real questions from their classrooms:

“I have a child who bites almost daily. I’ve tried staying close, offering teething toys, watching for triggers. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t. What am I missing?”

“Three families in my group are navigating really hard separations. I feel like I’m failing them. How do others handle this?”

“I’m noticing that the boys in my room seem to need so much more movement than the environment allows. How do I meet that need?”

The group doesn’t jump to solutions. Instead, they ask questions that help the educator see more:

What happens right before the biting?

What does the child’s body tell you about their state?

What helps you stay regulated when you’re anticipating the next bite?

What do you know about this child’s home experience?

What have you tried that worked even once?

They might observe in each other’s classrooms. They document patterns. They try different approaches and report back. Over time, they develop shared language for what they’re seeing and build collective expertise grounded in their specific contexts.

This builds educator capacity by:

Creating space to move from reactive response to thoughtful observation

Developing richer language for understanding children’s behavior

Building confidence through collegial problem-solving

Reducing isolation that makes demanding work unsustainable

Legitimizing educator knowledge alongside expert knowledge

What this involves:

Skilled facilitators with expertise in both infant/toddler development and adult learning

Protected time for monthly meetings (substitute coverage or built into schedules)

Commitment to multi-year participation—learning communities build trust and depth over time

Recognition that this IS professional development, not an add-on to it

Practice architecture dimensions addressed:

Language: Develops shared language and frameworks for practice

Power: Positions educators as knowledge-generators, not just mandate-implementers

2. Reflective Supervision

What this is: Regular (weekly or biweekly), protected time for individual or small group supervision that focuses on the educator’s internal experience as essential to responsive practice.

What this looks like in practice:

An educator sits with their reflective supervisor and talks about a child who’s been on their mind:

“There’s something about Maya that just… I find myself avoiding her. She clings, she whines, she never seems satisfied with what I offer. I know I’m supposed to see her as needing connection, but honestly, I feel annoyed.”

The supervisor doesn’t problem-solve or tell the educator what to do. Instead:

“Tell me what happens in your body when Maya approaches you.”

“Tension in my shoulders. My jaw gets tight. I feel myself pulling back even before she touches me.”

“What does that pulling back remind you of? Have you felt that anywhere else in your life?”

The conversation explores the educator’s response—not to psychoanalyze them, but to build awareness that allows for choice. When educators understand their own triggers and patterns, they can recognize them arising and make different choices about how to respond.

Another educator uses supervision to process the grief of a child transitioning out:

“I know I shouldn’t be this attached. But I’ve had him since he was 15 months. I know exactly how he likes to be comforted, what his different cries mean, how his face lights up when his grandmother picks him up. And now he’s moving to a new classroom and I feel like I’m losing something.”

“Tell me about that feeling of loss.”

The supervisor helps the educator honor the relationship, understand what made it meaningful, recognize how it’s shaped their practice with other children, and prepare for the transition in a way that serves everyone.

This builds educator capacity by:

Developing self-awareness that enables conscious response instead of reactive patterns

Processing the emotional demands of intimate caregiving work

Building capacity to stay regulated when children’s behavior is dysregulating

Creating language for internal experiences that profoundly shape practice

Providing consistent support relationship that models what we want for children

What this involves:

Reflective supervisors trained in infant/toddler mental health approaches (40+ hour foundational training)

Protected time that won’t be interrupted by program demands (60-90 minutes weekly or biweekly)

Organizational culture that values this as essential, not optional

Parallel support for supervisors—their own consultation to maintain reflective capacity

Practice architecture dimensions addressed:

Language: Legitimizes emotional and relational dimensions of work

Time: Requires protected time and trained personnel

Power: Reframes supervision as support rather than surveillance

3. Material Support: Environment and Transition Assistance

What this is: Recognition that material conditions—physical environments, staffing adequacy, transition capacity—enable or constrain everything else educators try to do.

What this looks like in practice:

Physical environment:

A program receives support to:

Create a cozy corner with soft lighting and comfortable seating where overwhelmed children (and educators) can retreat and regroup

Install low shelving that allows toddlers to see and access materials independently

Add sensory materials suited to oral exploration and tactile investigation

Create separate spaces for active play and quiet engagement

Design an entry area where families can linger during drop-off and pickup

Staffing and transition:

A program gets additional support during the first three months to:

Have extra hands during the most challenging transition times

Allow educators time to observe carefully before jumping in

Provide coverage so educators can have extended conversations with families

Bring in specialist consultation when puzzles arise

Enable educators to visit children’s homes before they start

This builds educator capacity by:

Removing environmental barriers to responsive practice

Allowing time for the observation and reflection that learning requires

Providing specialist knowledge when needed

Supporting the gradual relationship-building that two-year-olds need

Reducing physical and mental load so educators can be truly present

What this involves:

Needs assessment specific to each program’s starting point

Flexible resources that match actual needs, not one-size-fits-all allocations

Technical assistance for programs that need help envisioning adaptations

Timeline that allows modifications before implementation begins

Recognition that ongoing capacity (not just startup) matters for sustainability

Practice architecture dimensions addressed:

Time: Directly provides resources that enable responsive practice

Power: Signals that quality requires investment in conditions, not just mandates

4. Partnership Structures with Community

What this is: Authentic partnership where community-based directors, family child care providers, school administrators, and families share decision-making authority about implementation approaches.

What this looks like in practice:

A borough implementation partnership meets monthly. Today they’re discussing separation and reunion protocols:

A family child care provider shares: “In my home, parents come inside. We sit on the floor together, the child shows them what they’ve been doing. The parent doesn’t just drop and run. This is essential for trust.”

A center director responds: “We can’t have 15 families in our classroom at 8:30am. But what if we created a gradual entry period where for the first two weeks, parents can stay as long as they need?”

A parent adds: “What I needed was someone who would text me a photo mid-morning so I knew my daughter was okay. Just seeing her playing helped me trust.”

An NYC Office of Child Care and Early Education representative listens and asks: “What would support you in making these different approaches work? How do we write guidance that’s flexible enough to honor your different contexts?”

The group makes decisions about:

What flexibility exists in implementation timelines

How quality will be assessed (not just compliance with rules, but whether approaches build trust with families)

What resources programs need to adapt approaches to their contexts

How learning from their different approaches will be documented and shared

This builds educator capacity by:

Recognizing that educators hold essential knowledge about what children and families need

Creating pathways for educator expertise to shape policy, not just implement it

Building collective problem-solving capacity across program types

Shifting from defending against mandates to co-designing implementation

Developing shared ownership of quality rather than top-down accountability

What this involves:

Skilled facilitation that manages power dynamics and ensures all voices are heard

Compensation for community members’ time and expertise

Real authority to make decisions, not just advisory role

Transparent communication about what partnerships can and cannot decide

NYC Office of Child Care and Early Education willingness to genuinely share decision-making power

Practice architecture dimensions addressed:

Power: Redistributes power; centers community knowledge

Language: Creates space for multiple perspectives

Time: Allows resource decisions to reflect local priorities

5. Learning Networks

What this is: Small networks of 5-6 programs meeting quarterly to engage in rapid-cycle collective inquiry—identifying challenges, trying approaches, reflecting on results, and sharing learning. Start with 2-3 pilot networks in Year 1.

What this looks like in practice:

A learning network of six programs convenes quarterly. Programs share what they’re struggling with:

“Half our families want us to get toddlers fully potty trained. We don’t think that’s developmentally appropriate for most two-year-olds, but we’re getting pressure.”

“We have three children who are really aggressive with each other. We’ve tried staying close, we’ve worked on language, but we’re not seeing change and families are getting upset.”

“Our families all work multiple jobs. We never see them at pickup. How do we build relationships?”

The network picks one challenge to focus on collectively. For the potty training question, they explore:

What does research say about readiness signs?

How do others talk with families about developmental expectations?

What ARE we willing to support, and where do we hold boundaries?

What does this bring up for us about parent expectations?

Three programs volunteer to try different approaches over the next three months:

One creates a parent workshop on toilet learning readiness

One sends home observation sheets for families to track readiness signs

One has individual conversations with each family about their hopes and concerns

At the next quarterly meeting, they report back:

The workshop was poorly attended, but the materials were useful

The observation sheets sparked great conversations

Individual meetings revealed that most families just want to know their child will be ready before Pre-K

The network synthesizes: Family anxiety about next steps often drives pushing for early skills. When we address the underlying worry and share what we’re seeing in their child, pressure decreases.

They create a practice brief documenting this learning and share it with other 2-Care programs.

This builds educator capacity by:

Creating feedback loops so learning happens across programs, not in isolation

Distributing problem-solving instead of every program solving everything alone

Building collective knowledge base grounded in actual practice

Positioning educators as knowledge generators

Accelerating learning through documentation and sharing

What this involves:

Network facilitators with both early childhood expertise and facilitation skill

Documentation capacity to capture and share learning

Platform for making network products accessible to all programs

Protected time for quarterly participation (substitute coverage or scheduling support)

Quality process to ensure sound practices are being shared

Starting small: 2-3 pilot networks in Year 1, expanding based on learning

Practice architecture dimensions addressed:

Language: Creates practitioner-generated knowledge base

Power: Distributes problem-solving authority

Time: Shares solutions efficiently across programs

6. Family Partnership in Learning

What this is: Structured opportunities for families and educators to learn together about supporting two-year-olds’ development, built on the foundation that families are experts on their children and partners in caregiving.

What this looks like in practice:

A family-educator learning group meets monthly. Today’s topic emerged from several families asking about their children’s biting. Rather than educators presenting “solutions,” the facilitator creates space for families and educators to share observations:

A parent describes how their child bites when frustrated but doesn’t yet have words to express needs

An educator shares what she’s noticing about triggers in the classroom

Another parent asks: “How do you stay calm when it happens?”

Together, they explore: What helps at home? What helps at school? What language are we all using?

The group generates strategies that work across settings. Families learn what educators are trying. Educators learn family routines and approaches. Most importantly, everyone understands they’re working together—not receiving instructions from experts.

This builds educator capacity by:

Deepening educators’ understanding of individual children through family knowledge

Creating consistency between home and program approaches

Building authentic partnerships where families and educators learn from each other

Expanding educators’ repertoire through exposure to diverse family practices

What this involves:

Facilitators skilled in family-professional partnership (Division for Early Childhood, 2014)

Recognition that families and educators are equal partners with different expertise

Protected time for both families and educators to participate (compensation for educators’ time)

Interpretation services to ensure all families can fully participate

Childcare during meetings so families can attend

Connection to existing parent engagement structures in programs

Practice architecture dimensions addressed:

Language: Builds shared language between home and program

Power: Positions families as knowledgeable partners, not service recipients

Time: Requires investment in relationship-building

Envisioning the Recommendations in Practice

The following story illustrates what becomes possible when these elements work together.

Week 1: Carmen is a new lead teacher in a 2-Care classroom. She came from a 3-year-old room and is finding the transition harder than expected. When Mia screams and arches her back during diaper changes, Carmen feels her frustration rising. When Kiran follows her everywhere and melts down if she steps away, she feels suffocated. When three toddlers all want to sit in her lap at once, she doesn’t know how to meet everyone’s needs. The constant physical demands—lifting, bending, being climbed on—leave her exhausted.

6 weeks in: In her learning community, Carmen shares her struggle with diaper changes. Another educator asks: “What does Mia’s body tell you? When does the arching start?” Carmen realizes it’s always when she’s rushing, already thinking about the next child waiting. An educator who worked in infant rooms shares: “I slow way down. I narrate what’s happening. ‘I’m going to lift your legs now. Here comes the wipe—it might feel cold.’ When they feel respected, they relax.” Carmen tries this. Mia still resists sometimes, but not every time. Carmen notices her own breathing matters—when she’s calm, Mia settles faster.

3 months in: In reflective supervision, Carmen explores her response to Kiran’s clinginess. “He’s two and a half—shouldn’t he be more independent by now?” The supervisor asks what independence means to Carmen, where that expectation comes from. Carmen realizes she equates neediness with failure—hers and the child’s. The supervisor helps her see that Kiran recently transitioned from home care, his mom just returned to work, and he’s using Carmen as a secure base to explore this new environment. His following isn’t defiance or delay—it’s exactly what he needs to eventually feel secure enough to separate. Carmen stops trying to make him independent and starts noticing when he does venture away, even briefly.

4.5 months in: Carmen’s program receives environment adaptation support. They add a low climber and create a “heavy work” station with a wagon to pull, bean bags to carry, and a small push broom. Marcus, who was constantly crashing into other children, now has appropriate outlets for his sensory needs. They create a cozy corner with pillows where Carmen can sit during arrival time. Instead of standing and redirecting, she sits and holds whoever needs connection. Children cycle through—some stay for 30 seconds, some for 10 minutes. The physical changes mean Carmen isn’t constantly on her feet managing chaos. She can be present.

6 months in: In the borough partnership meeting, Carmen hears a family child care provider describe her separation routine: parents stay until their child shows them something, the child controls when the parent leaves. A center director says, “We can’t have 15 parents in our room at 8:30.” But what if they staggered arrivals over 90 minutes? What if some families needed 20-minute goodbyes for the first two weeks? The partnership agrees to let programs experiment with different approaches rather than requiring one drop-off protocol. Carmen’s center tries flexible arrival times. Some families need three weeks of staying before their child can separate. But by November, everyone has transitioned successfully.

8 months in: Carmen’s learning network tackles challenging behavior. She shares about Aisha, who bites—not when angry, but during high-energy play. Through the network’s inquiry process, Carmen starts observing patterns: Aisha bites when excited, when there are too many children in a small space, when she’s trying to initiate play but doesn’t have the language yet. Carmen tries new approaches: she stays close during active play, narrates what she sees (“You want to play with Sofia!”), teaches Aisha to tap a friend’s shoulder instead of biting to get attention, reduces the number of children in the block area. The biting doesn’t stop immediately, but it decreases. More importantly, Carmen understands what the behavior is communicating.

By the end of Year 1: Carmen has developed capacity she didn’t have before:

She understands that Mia’s resistance during diaper changes is about bodily autonomy, not defiance—and that slowing down and narrating respects her developing sense of self

She recognizes Kiran’s clinginess as secure attachment formation after a major transition, not developmental delay

She sees Aisha’s biting as communication about overstimulation and desire for connection, not aggression requiring punishment

She knows Marcus needs proprioceptive input—heavy work, climbing, pushing—to regulate his body and can provide appropriate outlets

She can read children’s cues and adjust her responses in the moment instead of applying the same approach to every child

She has colleagues who help her see patterns she misses alone

She experiences her knowledge as valued and contributing to collective understanding

This is what building educator capacity looks like. Not curriculum training. Not compliance monitoring. But infrastructure that develops the observation skills, developmental knowledge, self-awareness, collegial support, and material conditions that enable responsive caregiving.

Making This Real: What Implementation Requires

These recommendations require specific infrastructure decisions:

Facilitate learning communities and networks: Who will do this work? Skilled facilitation—people with deep early childhood knowledge and expertise in adult learning and group process. Options include:

The NYC Office of Child Care and Early Education developing internal capacity

Contracting with organizations specializing in practitioner inquiry and infant/toddler mental health

Training experienced educators to become facilitators

Partnership with higher education institutions

Provide reflective supervision: Who will serve as reflective supervisors? This involves specialized training and ongoing consultation. Options include:

Building reflective supervision capacity within programs (training directors/coordinators)

Creating a network of reflective supervisors serving multiple programs

Contracting with infant mental health organizations

Developing borough-based hubs where educators can access reflective supervision

Coordinate partnership structures: Who convenes and supports the partnership work? This involves dedicated coordination capacity and skilled facilitation. The NYC Office of Child Care and Early Education would likely establish this infrastructure.

Support environment adaptation:

Programs need accessible resources for physical modifications and materials. A well-designed grant process with robust technical assistance enables programs to identify needs and access support:

Competitive grant process with clear criteria

Technical assistance for application development

Consultation services to help programs assess needs and envision adaptations

Streamlined process that doesn’t burden already-stretched programs

All of this involves:

Multi-year commitment—this is permanent infrastructure, not temporary implementation support

Adequate investment—quality support costs money

Flexibility—different programs benefit from different approaches

Learning orientation—willingness to adapt based on what we discover

Cross-System Coordination for Children with Disabilities

Many two-year-olds entering 2-Care will have developmental delays or disabilities and will be receiving Early Intervention (EI) services or transitioning to preschool special education. Research shows that transitions between Part C (EI) and Part B-619 (preschool special education) are challenging for families, particularly when systems don’t coordinate effectively (George-Puskar & Bruder, 2018; Rous & Hallam, 2012). Recent federal policy emphasizes that creating inclusive opportunities requires partnerships between EI providers, LEAs, and community-based early childhood programs (U.S. Department of Education & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2023).

Building educator capacity for responsive caregiving requires formal partnerships between the NYC Office of Child Care and Early Education, the Department of Health (which oversees EI), and DECE. This includes:

• Joint training opportunities where EI providers, preschool special education teachers, and 2-Care educators learn together

• Transition protocols that ensure information sharing with family consent

• Learning communities that include educators across service systems

• Recognition that many educators in 2-Care settings will be supporting children with IFSPs or IEPs

The Division for Early Childhood’s Recommended Practices (2014) emphasize that transition requires coordinated cross-agency collaboration, not just individual program efforts. The tools and frameworks developed by transition researchers (Rous, Hallam, & Wolery, 2006) provide guidance for building these interagency structures. For 2-Care to serve all NYC children well, these system partnerships must be built intentionally from the beginning.

A Note on Implementation

These recommendations establish core infrastructure requirements, not implementation blueprints. The specifics—facilitator training curricula, documentation protocols, quality assurance processes, adaptations for different program types—require codesign with the people closest to the work.

With 2-Care launching in high-need communities in fall 2026 and scaling to universal access by 2028, there is time to build well—but only if infrastructure development begins now, in parallel with program planning.

Implementation should begin with a pilot that convenes:

Higher education faculty with expertise in infant/early childhood mental health and adult learning

Researchers who can document what works and what needs adjustment

Technical assistance providers with deep practice knowledge

Educators across program types (center-based, family child care, home-based)

Families whose children will be served

Program leaders who understand their communities’ contexts

This codesign group would develop implementation details grounded in NYC’s specific landscape—its workforce, its communities, its existing infrastructure. The practice architectures outlined here provide the framework; the people closest to the work determine how to build within it. What gets learned in the initial pilot communities shapes expansion—this is how quality scales sustainably.

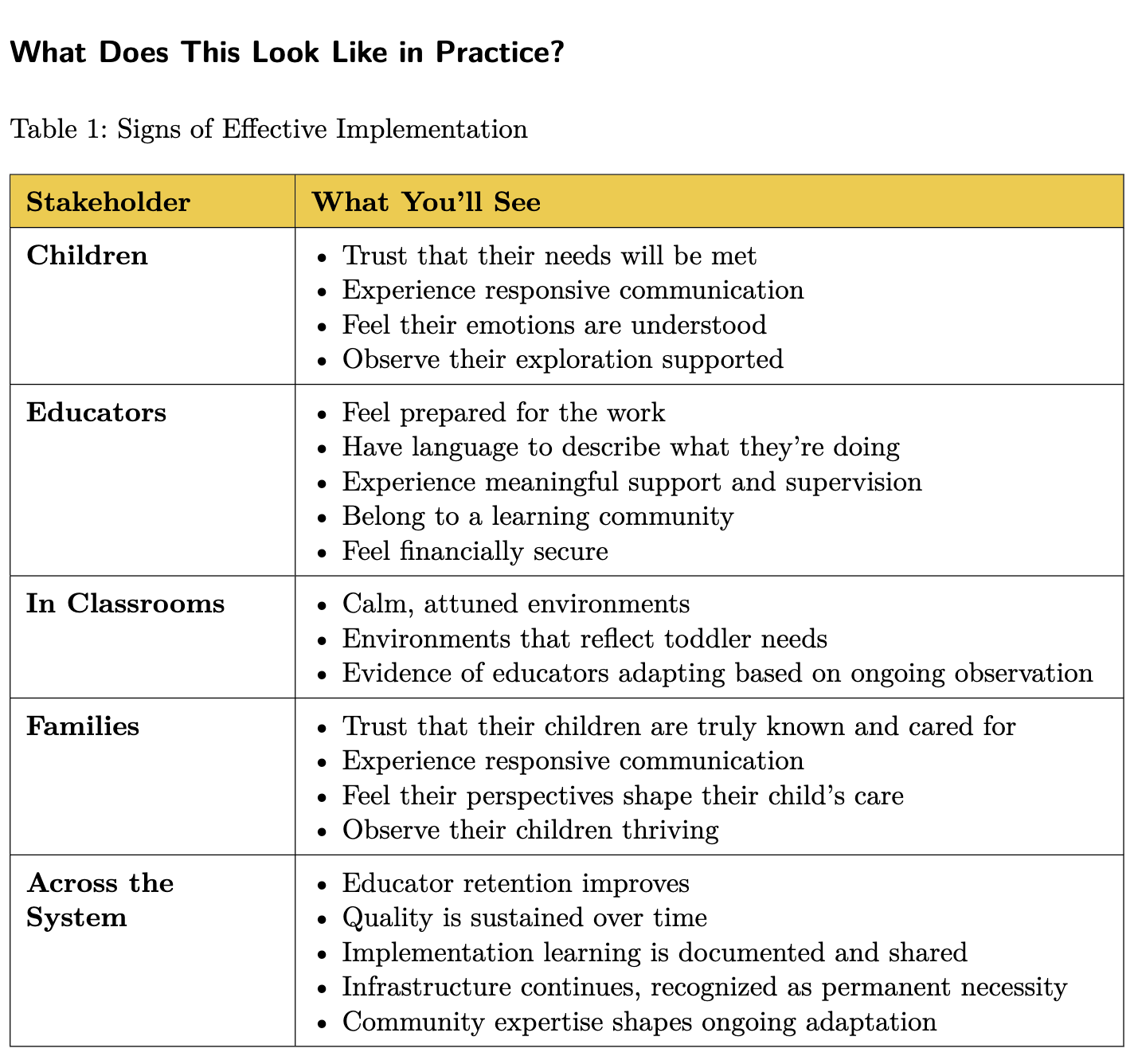

What Does This Look Like in Practice?

Strong practice architectures create observable changes at every level:

Table showing what effective implementation of practice architecture recommendations looks like across five stakeholder groups: children, educators, classrooms, families, and system-wide outcomes.

The Opportunity

NYC’s investment in 2-Care offers the opportunity to create conditions where educators develop into skilled, responsive practitioners who provide the relational, attuned care that two-year-olds benefit from. This happens when we build practice architectures that enable educator growth, not just mandate curriculum implementation.

The research points toward what enables educators to become responsive, attuned caregivers. The question is whether we’ll create the conditions that allow that development to happen.

References

Fixsen, D. L., Naoom, S. F., Blase, K. A., Friedman, R. M., & Wallace, F. (2005). Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature. Tampa: University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, National Implementation Research Network. https://nirn.fpg.unc.edu/resources/implementation-research-synthesis-literature

Division for Early Childhood. (2014). DEC recommended practices in early intervention/early childhood special education 2014. https://www.dec-sped.org/recommendedpractices

George-Puskar, A., & Bruder, M. B. (2018). Judgments of service coordinator practices and transition-related outcomes for children and families. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 38(1), 30-41. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271121418767179

Gilliam, W. S. (2005). Prekindergarteners left behind: Expulsion rates in state prekindergarten systems. Foundation for Child Development. https://www.ziglercenter.yale.edu/publications/National%20Prek%20Study_expulsion_tcm350-34774_tcm350-284-32.pdf

Jeon, H.-J., Kwon, K.-A., McCartney, C., & Diamond, L. (2024). Early childhood education and early childhood special education teachers’ perceived stress, burnout, and depressive symptoms. Children and Youth Services Review, 166, 107915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2024.107915

Joyce, B., & Showers, B. (1982). The coaching of teaching. Educational Leadership, 40(1), 4-10. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ269889

Kemmis, S., Wilkinson, J., Edwards-Groves, C., Hardy, I., Grootenboer, P., & Bristol, L. (2014). Changing practices, changing education. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-4560-47-4

Learning Policy Institute. (2024). Coaching at scale in early childhood education systems. Palo Alto, CA: Author. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/coaching-scale-early-childhood-education-systems-brief

Marshall, S. A., & Horn, I. S. (2025). Teachers as agentic synthesizers: Recontextualizing personally meaningful practices from professional development. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 34, 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2025.2468230

McCaw, C. T. (2023). Beyond deliberation—radical reflexivity, contemplative practices and teacher change. Journal of Educational Change, 24, 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-021-09432-4

Paradis, N., Johnson, K., & Richardson, Z. (2021). The value of reflective supervision/consultation in early childhood education. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 41(3), 68–75. https://www.zerotothree.org/resource/journal/the-value-of-reflective-supervision-consultation-in-early-childhood-education/

Rous, B., & Hallam, R. (2012). Transition services for young children with disabilities: Research and future directions. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 31(4), 232-240. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271121411428235

Rous, B., Hallam, R., & Wolery, M. (2006). Tools for transition in early childhood: A step-by-step guide for agencies, teachers, and families. Brookes Publishing.

Shea, S. E., Grimm, J., Stroud, C. B., Ammerman, R. T., Segar, K., & van Ginkel, J. B. (2020). Infant mental health home visiting therapists’ reflective supervision self-efficacy in community practice settings. Infant Mental Health Journal, 41(6), 856-873. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21839

Shonkoff, J. P., & Fisher, P. A. (2013). Rethinking evidence-based practice and two-generation programs to create the future of early childhood policy. Development and Psychopathology, 25(4pt2), 1635-1653. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579413000813

Tobin, R. M., Zinsser, K. M., & Lefmann, T. (2024). Reflective supervision and reflective practice in infant mental health: A scoping review of a diverse body of literature. Infant Mental Health Journal, 45(1), 5-23. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.22091

U.S. Department of Education & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2023). Policy statement on inclusion of children with disabilities in early childhood programs. https://sites.ed.gov/idea/idea-files/policy-statement-inclusion-of-children-with-disabilities-in-early-childhood-programs/

Wenger, E., McDermott, R., & Snyder, W. M. (2002). Cultivating communities of practice: A guide to managing knowledge. Harvard Business School Press. https://hbsp.harvard.edu/product/4591-HBK-ENG

Zaveri, M. (2026, January 8). Hochul and Mamdani to announce road map to expand child care. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2026/01/08/nyregion/mamdani-hochul-child-care.html

Zeng, S., Corr, C. P., O’Grady, C., & Guan, Y. (2019). Adverse childhood experiences and preschool suspension expulsion: A population study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 97, 104149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104149

Zinsser, K. M., Zulauf, C. A., Nair Das, V., & Silver, H. C. (2019). Utilizing social-emotional learning supports to address teacher stress and preschool expulsion. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 61, 33-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2017.11.006

Sarika S. Gupta, Ph.D., is the founder of Ecological Learning Partners LLC. Her work uses contemplative mapping to make visible the relational infrastructure that sustains learning communities. This piece builds on thinking developed in “What Makes Policy Sustainable? Practice Architectures for NYC’s Early Childhood Expansion” and “Building Relational Infrastructure: Questions for a Moment of Transition.”